In episode 14 of the series “Rowing Around Immráma”, we treated the Fenian tale, The Pursuit of the Gilla Decair and his Horse, as a kind of spoof Immrám. While this is the impression given, it also has another purpose.

One of the prime functions of Fenian tales is to illustrate that whatever genre its heroes happen to wander into, whether in the mortal or the Otherworld, they will prove themselves vastly superior in every highly regarded quality, (mostly feasting and fighting), to any person or power that they encounter.

If the tale tale may be seen as a ‘spoof’ Immrám, it is not a a parody. It is not merely making fun of the form. This Fenian story has generated a popular story in Immrám style, featuring some well-loved heroes. To be effective, a ‘spoof’ has to demonstrate familiarity with the established genre material. The Pursuit of the Gilla Decair and his Horse does just this.

This precipitous Fenian Immrám is launched after fifteen of Finn’s men have been snatched away on the back, or tail’s end, of a huge and ugly horse. Finn may have a gifted tracker in his company, but he and his men, in true Immrám style, row blindly for three days and nights. They find themselves facing a rocky island, with sides so high and sheer that it proves impossible for even these heroes to ascend. Only Diarmuid, after being taunted s a wimp, manages the climb; pole-vaulting up, using staffs given him by his foster-father Manannán. Even so, he is unable to find a way for the rest of the crew to follow.

Already, he has succeeded where other Immrám voyagers have failed to climb a ‘pillar island’.

The Uí Corra encountered a very similar island, (island 4). It had high sheer cliffs, but no landing place. They could hear ‘a great commotion’ from above, but could see nothing. Máel Dúin’s adventure includes a very similar island, (island 23). His pillar-island has a ‘locked door’ as a harbour. Máel Dúin’s crew can see people on top of the pillar, but are unable to converse with them.

That these islands are significant is re-enforced by the recording of an adjacent island, or ‘wonder’. Máel Dúin’s crew encounter a four-sided pillar draped in silver net. It is so high that they can see, neither, top or base in the clear sea. The mesh of the net is large enough for the boat to row through a single link. To prove that it is not an illusion, Diurán cuts a two-and-a-half ounce piece away. The Uí Corra also encounter a pillar-island, draped in a net of silver and findruime. Indeed, the text states that this is the same wonder encountered by Máel Dúin in his turn.

Brendan only encounters the pillar-island in its netted form, (island 13); although his ‘Island of Hell’, (island 15), had cliffs that were “so high they could scarce see the top, were black as coal, and upright like a wall”. The description of the netted pillar-island, has now reached fantastical proportions. The monks see a column in the sea, where the top is lost in the sky. It has a canopy made of some strange material like silver marble, stretching a mile out and deep into the sea. The sea is transparent and they can see down to the base of the canopy and the column. The pillar itself is clear crystal. The monks lower oars and pull themselves closer by holding onto the canopy, and try to get the boat into the opening. Brendan goes to great lengths to measure the island using sunlight and shadow.

The duplication of these islands is interesting. It seems that this island is significant enough to have a presence; both in the temporal, everyday world and the magical Otherworld. This transitional state is typical of the Immrám genre. In The Pursuit of the Gilla Decair, the island of the pillar is described in naturalistic – if exaggerated – terms; but is clearly a transitional portal to Otherworld adventures.

In our “Rowing Around Immráma” series, we made it clear that we do not regard the Immráma merely as fanciful travellers’ tales, based on actual voyages. We felt that they were multi-layered, capable of holding several interpretations. However, this view does not exclude descriptions of real, perhaps unusual locations, encountered by sea-going explorers. This “Island of the Pillar” may well reflect an actual island.

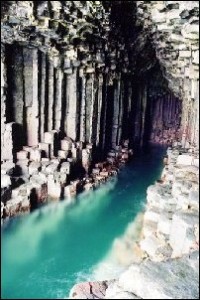

The island of Staffa is a small, now uninhabited, island situated not far from Mull; part of the Inner Hebrides in Scotland. The island is hardly more than a kilometre long and half a kilometre wide. It may be small, but it is geologically world-famous. Staffa is volcanic in origin, and its basalt layer cooled forming hexagonal crystalline columns, similar to those found on the Northern Irish Antrim coastline and known as the ‘Giant’s Causeway’. The island also has a number of sea caves, some containing basalt pillar formations. The best known of these caves is known as ‘Fingal’s Cave’. The island has no natural anchorage, but does have a fresh-water spring.

In modern times, the island was ‘discovered’ by the naturalist, Joseph Banks, who sailed with Cook on his first voyage in 1768. It was he who, initially, brought it to the attention of the public. Its growing fame attracted many famous tourists included Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Keats, Wordsworth, Turner, Robert Louis Stevenson, David Livingstone, even Queen Victoria.

Fingal’s Cave was a particular draw, although its associations with Fionn Mac Cumhaill, now detailed on every tourist website, were most probably the work of the eighteenth-century (so-called) translator and forger of Gaelic poetry, James MacPherson. The original Gaelic name for the cave was An Uamh Bhinn, “The Melodious Cave”, but it was renamed, or mistranslated, under the influence of MacPherson. After visiting the cave in 1829, Felix Mendelssohn wrote the Hebrides Overture, known as “Fingal’s Cave”. He is said to have been inspired by the strange acoustics in the cave.

Staffa, and particularly Fingal’s Cave, typified all that was required to make up the most attractive of eighteenth and nineteenth century Romantic landscapes. its popularity grew as a tourist destination throughout the nineteenth century, even though the travel challenges were considerable. Today is still only possible to visit Staffa in very calm weather conditions, much like the Skelligs off the Kerry coast.

It might have been re-discovered in the eighteenth century, but it was certainly ‘on the map’ much earlier. The Vikings knew it and gave it the name of “Pillar Island”, (after stafr – old Norse for ‘staff’ or ‘pillar’). It must also have been known to intrepid Irish sea-voyagers. Geographically speaking, it is not distant from the North-Eastern tip of Ireland. Islay, associated in story with Manannán. and Kintyre, where the fatal enemy of Mongán was located, lie only just to the South of Mull and Staffa.

This tiny inaccessible and spectacular island must have always been a place of uncanny mystery. Passing sailors might well have come back with tales of sheer rock precipices and regular shaped pillar constructions that, surely, were man made, perhaps castles constructed by giants. Then there were the great sea caves, like Fingal’s Cave, seemingly open to exploration, but forever closed to boats on closer inspection. Scrambling into the caves on foot, in their echoing darkness, must have been like stepping into an Otherworld portal.

With a model like that to draw on, it is hardly surprising that the “Island of the Pillar” appeared as a regular Immrám motif. Tales of its strangeness, its crystalline pillar formations, and its inaccessible, wondrous caves may have even inspired colourful, ‘Otherworld’ variants. Why should geology limit a fertile imagination?

Even so, we have to admire Finn and his friends. Only they could use such an Immrám motif as a launching point to victory over the “High-King of the World” and his elite soldiers, to surviving countless ‘Otherworld’ battles, plus plenty of extravagant feasting, and – oh yes – stealing the most beautiful woman in the world. Helen of Troy, eat your heart out!

If the island of Staffa was the inspiration for this tale, it was a good one.