How to define an Immrám

Series Four of Acallam na nÉces has been exploring the tale type, Immráma, that is ‘Voyages’. Immráma appear in the tale list which sets out the curriculum for the qualification of poets. This list sets out the five times fifty prime stories that any self-respecting bard should have ready, as well as the twice fifty stories allotted to the higher grades.

The class Immráma contains four tales. We have covered them in recent episodes, but this doesn’t mean that series four has come to an end. Our difficulty has been that there are several stories which could have been included in the class. First there was the voyage of Brendan the Navigator, which could not be excluded. There is also the fascinating and little known journey of Tadhg Mac Céin. This text will be the focus of our next episode. It is just too good to miss. Further, if Bran’s call to the ‘Isle of Women’, is classified as an Immrám, then how can we ignore the tale of ‘Niamh and Oisín’, or one of my favourite stories, ‘Cormac’s Cup’.

Oh, and I nearly forgot. We did say that we would take a look at the tales of Mongan, the ‘wonder child’ prophesied by Manannán in his call to Bran. So the series continues.

It all depends on how you define the class of tale. Immrám means ‘rowing around’. The journey must include an unexpected random quality that is undirected by the traveller himself. That does not imply that there is no outside agency involved. In our official Immráma, God, or Manannán, is a direct influence. The destination of the Immrám seems to be a place that is ‘other’, a quasi-geographical location only encountered outside every-day life. It is called by such names as Tír Tairngire, the ‘Land of Promise’, or Tír na nÓg, ‘The Land of the Young’, or even ‘The Land of Promise of the Saints’, a synthetic conflation of Christian and non-Christian ideals.

The Immrám is not a quest, as such. The hero does not attempt an incursion into the ‘Otherworld’ in order to achieve a specific goal or bring back a ‘boon’ to save his people. Bran is drawn into the adventure by the wonderful apple branch. He is chosen and does not actively seek the journey himself. Snedgus and Mac Ríagla, as well as the Uí Corra, enter on the voyage as a form of penance, and Máel Dúin is seeking vengeance, as is Tadhg Mac Céin. Only Brendan, an unofficial Immrám traveller, sets out deliberately to find the ‘Land of Promise of the Saints’. Even so, one version has Brendan setting out as a penance for destroying a ‘book of wonders’.

The destination is frequently less significant than the encountering of marvelous islands and wonders along the way. Many of these islands and wonders demonstrate the ubiquity of the Irish ‘Otherworld’. There are wonderful life-giving apples, rainbow rivers of salmon, glorious prophetic singing birds, knowledgeable women guides, as well as eternal summer and general immortality. However, the specifically Christian Immráma ‘balance’ these abundant isles with Isles of terror and punishment. For the monks, the reality of heaven cannot be visualised without the equivalence of hell. The wonders have become instructional and have to be paid for by piety.

Outcomes of Immráma are variable. It is only Bran, in the official Immráma, who is unable to return, owing to the Otherworld’s excessive time dilation. All the monastic groups return home, excepting a few individuals who are lost. Tadhg achieves the best of both worlds. He may return, after a human death, to his magical and immortal isle.

A Story-Teller’s Dream Ticket

When we first planned to undertake a Story Archaeology series on Immráma, I was keen to explore the guises in which the Immrám tale-type might appear in a wider world mythology.

The ‘journey’ story may be regarded as a universal metaphor for life. The mortal human sets out on an unknown sea of possibility, helped, or hindered, by external agency; alone or with companions who have their own destinies to follow, The voyagers will experience marvels along the way and may choose to profit from these encounters or to repeat mistakes made by themselves, or a companion. They may also hope for a future homecoming in this world, or another, making a good end. They will be changed, in some way, by the voyage.

The journey story may also be regarded as a story-tellers’ dream ticket. It is episodic, easily contained but not location specific, and anything may happen, however bizarre. It is a rollicking good story type. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that some of the oldest stories in the history of the world share factors in common with the Immráma.

Tales of the Flood

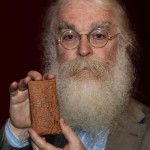

Let us examine one of the oldest stories ever to have been committed to the written form, that of the flood narrative. The story is probably best known in its Hebrew form, possibly compiled from Babylonian sources during or after the exile period. However, the oldest Sumerian documentation on cuneiform tablets is the best part of 4000 years old. Atrahasis (“Exceedingly Wise”) or Ziusudra, who later became Utnapishtim the Faraway (“He who has Life”), and, of course, the familiar Noah are all selected by the outside agency, Ea, Yahweh, etc. to save humans and animals from extinction. It is noteworthy that, in the pre-Hebrew versions, there is no suggestion that humans are to be punished for wickedness. It is merely that they are making too much noise. Ea (or Enki) sets out to save mankind in spite of the divine decision. The over all story is familiar to most people but there are some general connections to Immráma:

- It is an undirected voyage

- It is brought about by external agency

- It has prophetic birds, in that their sending out from the ark predicts dry land

- The destination is a re-born and promised land. Both Sumerian and Biblical king lists divide their histories into ante- and post-diluvium ages

- There are no on-voyage islands and wonders, however, unless you try to imagine how “Noah accommodates animals as divergent as lions and woodworm!”

In his book, ‘The Ark Before Noah’ [1] – (a Story-Archaeological exploration if ever I read one!) – Irving Finkal, assistant curator of Assyriology at the British Museum, has some interesting comments on the ‘arks’. He is convinced that the original descriptions given in Sumerian and Babylonian versions of the story, including the recently translated ‘ark’ tablet, show that the boat was thought of as round. What was being described was a coracle. It was an extremely large one, certainly, but in other respects similar to those used in Iraq from ancient times until the middle of the last century. They were either built from plaited palm leaf fibre rope, on a willow or similar frame, or covered in tanned hides, waterproofed with pitch and lard. So they were not so different from our Immrám boats then, just much larger. Of course, I am not suggesting that there is any link whatsoever between the Immrám texts and ancient Akkadian cuneiform, although our monks would have been familiar with the Hebrew story and would have recognised its applicability. I can imagine them keeping an eye out for rainbows on their travels between rocky island monasteries, just in case.

Argossys and Odysseys

There are, of course, other Classical Immrám-style voyages. Whereas the epic poem ‘ Argonautia’, the voyage of Jason and his ship companions, (created in the 3rd century BCE by Apollonius of Rhodes), is strictly a quest tale, it does share the Immrám-like encounters with strange islands and wonders. On the other hand, the earlier ‘Oddesey’ by Homer has more in common with the Immráma. Odysseus’ random travels begin after the commands of a god have been disobeyed by one of his companions. Aoelus gives Odysseus a bag holding back all the world’s winds, except the favourable west wind. One of his men opens the bag, thinking it contains treasure.

On his undirected journey, the hero encounters more than one ‘Isle of Women’ and experiences many marvels. However, there is no specific final ‘Otherworld’ destination. His goal is his long lost home and wife.

One of the defining qualities of the Immráma, as stated above, is the unexpected undertaking of a guided tour of the worlds beyond our own. This journey is both dangerous and life-altering. The traveller’s viewpoint can never be the same again. However, other cultures have not always thought of setting their ‘afterlife destinations’ on off-shore islands. They were, instead, traditionally located deep underground. An Immrám, then, would have to be to directed to an ‘Underworld’ rather than an ‘Otherworld’.

Dry-Land Immráma

At least one of these ‘dry-land’ Immráma could well have been known to our educated monks, who were familiar with Latin language and literature. A copy of the Aeneid exists among the early medieval Irish texts.

Book six of the Aeneid [2] involves Aeneus in a trip to the Underworld. He is guided by a woman, the Sybil, and must carry a golden-leaved branch if he is to gain entry. It is of interest, although there is no definable connection, that Bran and Cormac’s apple-branches have leaves of silver. He is guided through the world of the shades,observes the Elysium Fields, and has the horrors of Tartarus described to him. His dearest wish of meeting his father is achieved.

Now it is worth noting that, before Aeneus’s trip to the Underworld, he also experiences a time of wandering on the sea. In fact, his relationship with, and abandonment of, Dido of Carthage has some resonance with the story of Máel Dúin and his encounter with the Queen of the island.

When we discussed the voyage of the Uí Corra in episode 3, we compared their dark journey of the soul and their search for forgiveness with Dante Alighieri’s Inferno [3], written in the early fourteenth century. This first section of ‘The Divine Comedy’ is a voyage downward, deep into a pit, rather than across an unknown sea. Dante’s journey, guided by the poet Vergil, is as much a product of its time as the text of the Uí Corra, with its contemporary Céile Dé influence. It is also to be remembered that Inferno represents only one third of the poem. Dante balances his vision with Purgetorio and Paradiso, as the monks balance their encounters with the heavenly and the hellish.

From the fifteenth century allegorical morality play, Everyman, to John Bunyan’s evocative The Pilgrim’s Progress, published in 1678, the ‘dry-land’ Immrám story-type continued in popularity – without the rowing around, of course. I have always been fond of Pilgrim. I was brought up with the book. As a child, I valued the idiosyncratic characters and dramatic locations, the Slough of Despond, the Interpreter’s House, the Delectable Hills and the fight with Appollyon. It is not sophisticated, but it does have an engaging and robust quality which renders the story memorable. I always thought of it as a prototype fantasy novel, but it certainly shares similarities with the class of Immráma. A summary of The Pilgrim’s Progress might be given as follows:

A group of like-minded travellers cut themselves off from the world-we-know and encounter challenges and wonders along an unknown and winding path. They are directed by an external agency in their journey to another world. Friends are lost along the way, and they frequently miss their direction or become diverted. Some reach their destination. They do not return.

It lacks only the boat!

The Immrám in the 21st century

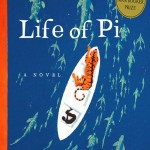

In episodes four and five, we explored the story of the Voyage of Máel Dúin. We compared his journey to the book The Life of Pi. This book by Yann Martel, published in 2001, won the Booker prize the following year. Since the film was released, the narrative of the novel has become relatively well known. [SPOILER ALERT!!] The protagonist is a young boy of sixteen years who adopts the name PI to avoid an unfortunate given name. His unusual childhood involves his father’s zoo in Pondecherry. After his father sells the zoo and is shipping the animals out, Pi is involved in a shipwreck where his family are lost but which he survives. He travels for two hundred and seventy seven days in a small boat with a ferocious tiger who has eaten the other surviving animals. He encounters many marvels, including an island with carnivorous plants. Later in the novel, he answers accusations that his story is unbelievable by offering a version where he has been terrorised by an evil cook who cannibalised his own mother. Pi is saying that, if life is a story, then the way you tell it is part of its truth.

This novel has very close ties with the Immráma. Pi is cast out into the unknown and swept away on an undirected journey. Without doubt,he experiences wonder and terror. His destination is safety, the ‘Promised Land’, where the hideous nature of his ordeal can become a transformative story. In episode six, while discussing the Brendan narrative, we also considered that the journey might, in part, be a parable of monastic life. It is not just the story – it is the way you choose to tell it. Yann Martel said, in an interview he gave in 2002,

I was sort of looking for a story, not only with a small ‘s’ but sort of with a capital ‘S’ – something that would direct my life. [4]

His response suggests that the act of writing the novel was something of an Immrám for him.

The most natural home for current Immrám-style stories may be Science Fiction. Instead of a small ship cast adrift onto the limitless sea, a craft may find itself lost and isolated in the endlessness of space, Sci-Fi depends on tales of wonder and terror which abound on imagined alien planets. The genre is able to offer a location which is immediately ‘Other’. A wide range of social and ethical issues may be addressed within this ‘otherness’, cut off from the mundane world, in the same manner as the voyage of Máel Dúin, for instance.

One readily found example might be Star Trek: Voyager, which plunges a ship and its crew off course, (whether with external agency or not is uncertain), and leaves them wandering on the stormy seas of an unknown sector of the galaxy. Their destination is the Promised Land of home, and they experience wonders and horrors on the islands in space that they encounter. Having watched as many episodes as I can handle, I am not convinced that they learn much wisdom from their unexpected interactions with other beings. I suspect that, in any case, the creators of Voyager might acknowledge a debt to Homer’s Odyssey, but would not be aware of any resonance with the Irish Immráma!

However, if I were to choose one example of a modern Immrám, I would select Douglas Adams’ inspired radio series, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy [5]. When you have, like Arthur Dent, been cast out into an uncaring universe because your planet has just been disintegrated to make way for an intergalactic bypass, and you have had to hitch a lift on a passing spaceship without having time to even pack a towel, and your only guide is an electronic book that describes Earth as “mostly harmless” – well, that’s a definite start to an Immrám. When you have encountered a talking drinks machine that offers something that is almost, but not exactly, entirely unlike tea; or the heaven of a ‘Pan-galactic Gargle-blaster’ served in the ‘Restaurant at the End of the Universe’; when you have encountered wonders and horrors such as surviving the ‘Total Perspective Vortex; or a space liner delayed for one thousand years waiting for a delivery of lemon soaked napkins; when you have reached the ultimate destination and met the ‘Ruler of the Universe’, who inquires whether you have come to sing to his cat: then you have been experiencing an Immrám.

It is a bizarre vision and yet offers a wonderfully wry look at the human condition. I think those adventurous and hardy monks might have enjoyed it. During one of Arthur Dent’s happiest interludes, he discovers – or remembers – how to fly:

“There is an art” he said, “or rather, a knack to flying. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss”.

Maybe those trees of singing birds had another message for our monastic voyagers.

A Final Thought

I hear that Skellig Michael will feature in the next Star Wars film, Episode Seven (or is it three and a half? ) So, the Jedi will be on what could have been Mernóc’s isle.

Immráma and Science Fiction ? Hmm!

Footnotes and References

[1] Irving Finkal, The Ark Before Noah

This book is hugely enjoyable and extremely informative. If you enjoy archaeology through texctual excavation and love a good story as much as we do, then read this book. Preferably listen to the audio book. The experience is greatly enhanced by the author’s enthusiasm and scholarship as he reads his own work. Highly recommended.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Ark-Before-Noah-Decoding/dp/1444757059

[2] Vergil, Aeneid, Book vi

http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/VirgilAeneidVI.htm

[3] Dante, Inferno

http://www.fullbooks.com/Dante-s-Inferno.html

[4]

Martel, Yann (11 November 2002). Interview with Ray Suarez. PBS Newshour.

[5] Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

If you haven’t encountered Hitchhiker, it is never too late. Go for the radio versions as well as the books. They are different. SHUN the film!

Bonjour.

j’ai baptisé “MERNOG” mon naomhog currac’h.

dans les EC’HTRA et IMMRAM je ne cherche pas des Dieux, Déesses et autres motivations de l’esprit humain .

je cherche , comme chercher une aiguille dans un botte de foin, les détails de navigation, de construction des barques.

les plus vieux récits parlent de barques tressées recouvertes de peaux. De 3 épaisseurs de peaux pour se protéger des vers qui vivent dans la mer.

ensuite la technologie évolue vers le cuir.

les plus vieux récits disent que les héros jettent leurs rames à la mer pour que la pénitence soit plus grande. leur barque étant dans les mains d’une divinité!!!

DONC la voile n’est pas pratiquée .

l’Abbé BRENDAN , sur les conseils de l’ermite FINN BARR part chercher “la terre promise aux saints ” . Il fait connaissance avec MERNOG (FILLI de FINN BARR ???? un druide ?) de là ils partent vers la “terre promise” et pour ce faire “”affronte un événement météorologique que seul le Golf du MEXIQUE produit.

(((si un jour vous passez par PLOUGASTEL DAOULAS dans le FINISTERE de BRETAGNE , je vous ferais essayer les coracles, MERNOG et le SANT EFFLAM ) actuellement BRIOG est à DALE… MILFORD HAVEN ;;; CYMRU )) KENAVO