Underworld, Otherworld: Introduction

There are, as we have frequently noted, only four official members that can be strictly classified as Immráma . These are, of course, Immrám Brain Mac Febul, Immrám Snedgussa ocus Mac Ríagla, Immrám Uí Corra, and Immrám Curaig Máel Dúin .

However, series four has already reached podcast episode 13 the longest series that we have undertaken, . It would seem that the story set was not as narrow as it, at first, appeared. Over the series, we have also been led to explore a whole vista of connected themes that have appeared, like extraordinary islands demanding research and further investigation.

Tadhg and his crew view Manannán’s sumptuous world with delight. But the poet of this little known gem takes equal pleasure in celebrating the diversity of the up-and-coming Christian world, with a vibrant enthusiasm and a double helping of humour. Not all such voyagers share Tadhg’s open mind.

The Immrám, tale is indeed transitional. It moves from the security of the ‘known’ to the uncertainty of the ‘unknown’ ocean, aware of the challenges and opportunities facing an adventurous seafaring race. Equally the tale set stands on the border between the heroic past and the Christian future, already demonstrating an equal diversity.

The Immráma ‘sea’ may also reveal deeper, themes, rising like Iasconius, the great fish, from the depths. For some voyagers, a world of pleasure and luxury may be a gift, for others, a temptation. Some see joy, others find hell. All see marvels and wonders. The Immrám, also contains the oldest theme of all, that of the journey of the soul through life. In a previous article, (Immráma in a broader mythological context) I suggested that the Immrám, had much in common with one of the earliest tales ever recorded. This is the voyage of Attrahassis the wise; more familiar to most of us in the guise of the Hebrew, Noah. Irving Finkel in his book “The Ark Before Noah, Decoding the story of the Flood”, notes, with interest, the unique vocabulary used to describe both the animal rescuing ark and another ‘basket’ ark, the cradle of the baby Sargon, left to float alone in a river reed boat. The earliest ark form, Finkel informs us, was woven from reeds and baskets shaped, round like a modern coracle, or a gigantic cradle.

The destination of these basket ‘arks’ is not of prime importance. They are intended to preserve life in whatever direction the storms of life may drive it. This, of course, does not preclude the pre-destined direction of an ‘outside agency’. Many of our Irish Immráma do have intended destinations although the travellers generally abandon themselves, at some point, to the hand of destiny, usually God.

However, the prevailing world view radically alters the desired destination in this transitional story form. Bran encounters the pleasures of the Isle of Women and shows little regret in abandoning himself to its eternal abundant summer. Máel Dúin encounters the same Land of Promise but the ‘work ethic’ of his crew demand a costly escape plan. Finally Brendan eschews all female company in his “Land of Promise of the Saints”. Nothing happens in this anti-climactic destination. The central image of his journey is the forcible dragging of a ‘brother’ down to hell, already burning with eternal fire as he is carried away screaming.

The true Irish Otherworld, with its ignorance of original sin and death, its life, health and beauty is lovingly described in many a story. It may be found on an offshore island or approached through a cave entrance or even a thick mist. Although it may be entered by travelling underground, it is no underworld. You don’t even necessarily have to die to get there, although it may prove difficult to return, owing to time dilation. There is no judgement, in the Christian sense, although you may be given tasks or quests. Women are usually wise, and beautiful, and all men are heroes. You may meet the Ever-living Ones, Manannán, Midir, Fand, Étaín, and others who will appear in a variety of splendid guises.

So on one hand, we have a sumptuous and scintillating summer, Otherworld and another focussed on of suffering and judgement. Which idea came first and what the journey was involved? This article, in two parts, will plot alternate routes, the Underworld route and the Otherworld route.

I will show you fear in a handful of dust “The Wasteland”:T.S. Elliot 1922

Underworld

Shaeol, Kur, Hades, these are terms that, if you are at all familiar with mythology, evoke underground caverns of dust, darkness and a drab meaningless existence.

Shaeol is, of course, the ancient Hebrew place of dust, synonymous with Abbadon, the pit of death. Kur was the equivalent destination for ancient Mesopotamians. This was a region of dust or clay deep below the earth’s surface. It was not a place of damnation for the wicked but merely a place for the dead. Of course, if you were wealthy with dutiful descendants, you could improve your lot with offerings left by the living.

The Hellenic Hades was much the same. According to the Odyssey, mostly an oral tale stories compiled under the name of the poet, Homer in the 8th century BCE, not even the greatest hero could escape his fate.

Achilles tells Odysseus

“Don’t try to reconcile me to my dying. I’d rather serve as another man’s labourer, as a poor peasant without land, and be alive on Earth, than be lord of all the lifeless dead.”[i]

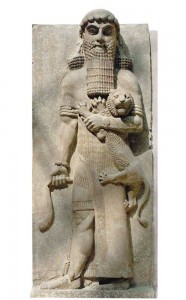

The epic of Gilgamesh, reflects similar attitudes to the dusty dry Underworld. Enkidu dreams of his forthcoming death and tells his friend, “He took me down to the dark house, to the dwelling where those who enter cannot ever leave, where dust is their food and clay is their bread…. They see no light and they dwell in darkness.”( ii)

Little is known about specific Hittite beliefs although the Canaanite (Ugaritic)Underworld was also a grim place of dry dust.

So, how do the bronze-age tale tellers cope with this somewhat ‘down to earth’ attitude to death where bodies are put into the ground and demonstrably return to dust? What stories of hope can they offer? It is interesting that so many ancient cultures came up with a similar solution. They each, eventually, provide a hero, or heroine, who has the strength and determination to go down, alive, into the dead Underworld and bring back boons or, at least, ameliorate conditions for those who will follow after.

Perhaps the earliest example is Gilgamesh, himself. Even in the Sumerian poems dating to 2100BCE. The gods appoint Gilgamesh Lord and Judge of the Underworld. He cannot escape eternal existence in the dusty darkness but his favour will improve conditions for those who have made regular offerings to him though out their lives.( iii)

Inanna, Baal, Orpheus, Persephone, Osiris and others, all make this dark journey. Apart from Orpheus, who attempts to return with his dead wife, Euridice, and this is a later example, they do not embark on this terrible path for altruistic reasons. Baal is invited to dine in the Underworld and cannot refuse. (iv) Persephone is stolen away by Hades. It is unclear why Inanna initially travels into darkness, but while she is away summer cannot return to earth.

So, the tellers of tales offered some hope, at least. If you could not, escape the grim dust of the Otherworld after death, at least that terrible place would never engulf the lands of the living. Spring would always return. However these stories were not promising personal salvation for the dead. They were more about keeping the ‘land of the living’ separate from that of the dead.

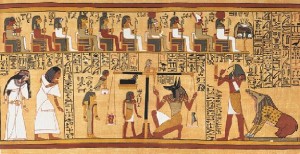

The ancient Egyptians had a different idea of the Underworld, at least for the rich elite in society but they, too, had an Underworld judge who might lend a sympathetic ear to the recently living.Osiris is probably the best exemplar of both the promise of continued fertility and abundance in the world of the living and the judge who ameliorates the dangers of the Underworld for the newly dead. Osiris is a legendary king / culture hero / demi god who gifts Egypt with agriculture and civilisation. He survives a lifelong battle with his brother Set, who represents the storm and desert that surrounds the fertile ‘black lands’. He is competently aided by his, magically wise, sister/wife, Isis and leaves a dutiful son, Horus, to avenge him. The Underworld in which he later rules is not a place of dust but is lush and green, much like an idealised fertile Egypt. However, you must still pay your way there. If you do not wish to work, like a peasant in the fields, you must take servants, generally in the form of models, ushabti (shabti or shawabti) figures. You must also ensure that offerings of bread, beer and all good things are regularly made at your tomb. But there is one more thing before you can achieve this Underworld existence. You must pass the judgement before the throne of Osiris. This is not just about being recognised by the judge because you made rich offerings to him in life, as is the case of meeting the judge, Gilgamesh. No. This is a judgement made on the way that you have lived your life. .If your heart is heavier than the feather of ‘Maat’ (truth / honour / natural justice) then you will die the final death and be eaten by the devourer.

Of course, as said earlier, it was mostly the rich who got to enjoy these eternal benefits. The ‘royals might even get to play among the stars. However, a poor Egyptian peasant, destined to desiccate in the desert sand just had to hope for the best. Even nobility with their highly decorated mastabas, built their ‘houses of eternity’ as close as possible to the tomb of a recent pharaoh, just to hedge their bets.

However, the life loving Egyptians quickly had the problem of passing the judgement hall under control. From the time of the Old kingdom, spells and wards were provided for the properly equipped mummy to aid the Ba, the personal soul that cannot wholly leave the body, on its night journey until it can be re-united with the Ka, the eternal spirit. The earliest formulae for negotiating entrance to the Underworld are found at Maedum, in the pyramid of Unas, last of the 5th dynasty pharaohs. They date back to around 2400BCE.(v)

These formulae for survival continued to develop into the period of the New Kingdom. The papyrus of Ani, acquired by E Wallace Budge dating to around 1200BCE, illustrates the judgement process clearly. (vi) The Scribe, Ani, is brought before Osiris. The great scales with the slathering monster ready to gobble up the heart weighted down with evil-doing is central. However, the soul is well prepared. The deceased has undergone the proper process of mummification with all the necessary funerary ritual. He or she is ready with the correct responses including the essential ‘negative confessions’.

“I have not swindled offerings.

I have not stolen from any God or Goddess.

I have not told lies.

I have not carried away food.

I have not cursed.

I have not closed my ears to truth.

I have not committed adultery.

I have not made anyone cry.

I have not felt sorrow without reason.

I have not assaulted anyone.

I am not deceitful.

I have not stolen anyone’s land.

I have not been an eavesdropper.

I have not falsely accused anyone.

I have not been angry without reason” ….. There are forty two negative confessions in all.

If all else fails, the soul will even know the spell to prevent his own heart speaking out against him or her.

Similar rituals continued in Egypt for more than two thousand years although Jan Assmann (vii) suggests that no canonical version of the ‘Book of the Dead’, or the ‘Book of Coming Forth by Day’, ever existed until the late temples of the Persian and Greek period began to contain elements of a deliberately selected cannon. Until then, many versions existed simultaneously.

It was not until around the sixth century BCE that conditions began to improve in Hades, at least for the virtuous although there do seem to have been some concessions. The idea of a more positive destination was available, perhaps influenced by Egyptian expectations. Although Homer, as stated above, consigns Achilles to the grim purposeless Underworld, he does offer Menelaus, husband to Helen of Troy, an alternate destination.

Proteus says

“The Deathless Ones will waft you instead to the world’s end, the Elysian fields where yellow-haired Rhadamanthys is. There indeed men live unlaborious days. Snow and tempest and thunderstorms never enter there, but for men’s refreshment Oceanos sends out continually the high-singing breezes of the west All this the gods have in store for you, remembering how your wife is Helen and how her father is Zeus himself. “

Menelaus is cheating fate by virtue of his father-in-law’s divine status! This may be the earliest mention of something akin to the descriptions of the Irish Otherworld but it is uncommon.

Hesiod, who is probably lived not long after the dates attributed to Homer, offers similar hope to worthy heroes who have been killed in battle. (viii)

Gradually, the Elysian Fields became available for the generally worthy, not just national military heroes. However, this left a need for a place where the ‘unworthy’ could be punished. Tartarus became a realm deeper under the ground, lower even than Hades. Originally, it was a place where monsters, or others, who had been defeated by the gods could be imprisoned.(ix) Certainly by the Roman era, it had become a place of general punishment after death.

The Hellenic world was also influenced by Zoroastrianism which emerged in the Persian dominated lands in the mid-fifth century BCE. Zarathushtra, or Zoroaster, from the Greek form of the name, probably lived around 650BCE although somewhat fanciful, much earlier, dates are sometimes claimed for him. He may have founded the belief system or codified an emergent set of attitudes and rituals. The earliest written information about Zoroastrianism comes from Herodatus, a resident of Hallicarnasus in Caria, (modern Bodrum, Turkey). Cicero may refer to Herodatusas “The Father of History”, but the writer of “The Histories”, was something of a tourist and travel writer. Wherever he went, he gathered folklore and stories organising them into structured information.

He left us much information concerning life under the Persians including their insistence that a meal without desserts was an unfinished and disappointing affair. The Persians considered Greek cuisine deficient for this reason! He also wrote about Persian religion giving glimpses of 5th century BCE Zoroastrianism in practice. (x)

In Zoroastrianism, which still exists as a faith today, good and evil are separate and opposed, having distinct sources. The ‘creative spirit’ Ahura Mazda is represented by the Amesha Spentas and the host of other Yazatas who constantly battle to save creationfromAngra Mainyu (Ahriman) the “destructive spirit”. Men and women are considered to have free will and are given a choice to support the eternal battle between the good (creative) and evil (destructive) principles. After death, those for whom the balance of thoughts and deeds have supported Ahura Mazda cross the bridge to his palace to continue the battle. Those whose evil deeds outweigh the good, descend to a place not unlike Tarturus or the Christian hell. However. This is not final. They may still alter their fate.

It has been claimed that Zoroastrianism is the first monotheistic religion. If it was not originally monotheistic, it certainly became so later allowing a ‘supreme creative spirit’ to oversee an eternal dualistic conflict. It was also influential in that I saw all mankind, whatever their status in life as equal in death. Neither wealth nor knowledge of magic would buy your passage.

So it does seem, by about the 5th Century BCE, an afterlife, mostly to be found in an underworld environment, was to be available to a wider cross section of society, but that a judgement on the life lived by the deceased had to be expected.

So far, our Underworld examples have all been taken from civilisations which left written, and pictorial, records for us to examine. If we were to seek for an insight into earlier Neolithic or even Mesolithic belief systems, what might we uncover? Our oldest (pre. 2000BCE) examples, so far, offered a somewhat grim expectation of a meaningless continuance in a dark and dusty underworld realm. What if we were to go back further?

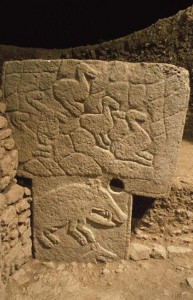

Since the late 1990’s, Klaus Schmitt has been leading the team that is excavating some of the oldest known man-made structures on earth. Gobeki Tepe, in Eastern Turkey, is a spectacular site. Schmitt has uncovered a series of circular enclosures each delineated by stone walls and T shaped, rectangular stone pillars. Each is finely dressed and many are superbly carved with animals, some in haut relief. The enclosures often have two central dolmans, far larger than outer ones, others have stone basins. The decoration is startling. There are friezes of birds, boars, snakes and what Schmitt describes as foxes. The row of little duck like birds at the base of one of the central dolman stones is particularly engaging. There are also human figures depicted but these geometric stylised figures are in stark contrast to the naturalistic representation of the animals. What is most remarkable, of all, is that these structures are between nine and twelve thousand years old. (xi)

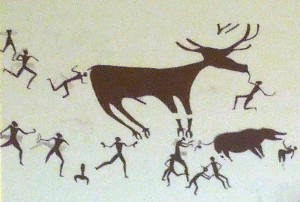

Could they have been places of sympathetic magic, intended to attract or celebrate the gifts of the animal world? This has been one suggested purpose of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic, cave paintings/ possibly the best known example would be the Lascaux cave system (17,000 BCE) (pictures) The animal carvings could have been designed to illustrate ancestor ‘kin’ groups, or to represent ‘foundation’ stories, explaining how the world came to be. Surviving indigenous Australian Dreaming tales’ have this same quality. xii They not only tell how specific features of the landscape came into existence, they also teach the importance of retaining the natural order of this ancestor created land and the human activity connected with, and located on, these important places. Their ‘cannon’ of stylised animal and human figures are a library containing a wealth of history, geography, law, and cultural identity. It is not impossible that the Gobekli Tepe structures served a similar purpose. Klaus Schmitt reminds us that we can only guess at an answer. We lack cultural references to offer more than speculations. However, there is absolutely no evidence for the speculation that the people of Gobekli Tepe, were worshipping mysterious sky gods or the albino offspring of fallen angels! Klaus Schmitt has had to deal with such unfounded speculations.

Gobekli Tepe, from current excavation information, can tell us little, if anything, about its people’s ‘afterlife’ beliefs. There has been no evidence of regular habitation or burial of the dead on the site. Çatalhöyük near Konya, also in Turkey, has more of a story to tell in this regard. Çatalhöyük was continuously inhabited between 7000 and 5000 BCE, one of the earliest known ‘towns’ It is a wonderful place to visit, although most of the wall paintings uncovered have had to be moved to safe display elsewhere. Here hunter-gatherers were among the first to settle, soon after the last ice age, domesticating animals and plants. The site was first excavated in the 1960’s by James Mellaart before Ian Hodder became project director in 1993.( xiii)

The individual houses, clustered together changed little over 1400 years. There were no streets separating them and the only entrance was via a ladder on the roof. Houses are different in size and decoration. Some of the houses, referred to by Ian Hodder, as ‘history houses’ might have been in use for a longer period or have more burials under the raised platform designed for that purpose, but this did not seem to give them a higher status. There were no areas that could indicate use by a ruling elite. Indeed, in his lecture, ‘The Leopard Changes his Spots’. (xiv) Ian Hodder comments on bone analysis indicating an equity of diet and resources between all groups including gender groups. He also has some very interesting evidence on the practice of fostering of children to other family groups, a practice also found in ancient Ireland. Maybe that custom was old indeed! Finds at Scara Brae indicate a similar egalitarianism.. (v)

What evidence there is, points to ‘down to earth’ cultures who honoured their ancestors and culture heroes, keeping them close. These were peoples who knew how to make the most of everyday resources including the deceased, who could remain a part of the living world. In spirit form, whatever that might be, they would retain an interested influence in the life of the tribe.

Certainly ritual and ceremony seems to have played a central role in their lives but I have wondered whether the impulse to trade, including cultural trade, rather than worship, might have provided that first requirement for jointly held gathering places. There is plenty of ritual attached to the process of trade and plenty of ways in which the ever-present Ancestors and their kinship identities could have provided welcome support.

So, to recap. The options for an afterlife, according to the examples examined so far, would seem to be either, if worthy, join the ancestors, an ever present, if somewhat nebulous collective, (and expect your bones to get moved around a bit) or to endure a purposeless existence as a dusty shade. If you have paid sufficient attentions to whatever culture hero acts as Underworld judge in your part of the world you might be able to procure favourable treatment. Alternatively, you could ensure that you have sufficient dutiful descendants to provide you with the symbolic food to relieve the tedious Underworld diet of clay. If you are fortunate enough to have been born a wealthy Egyptian, your outcomes could be brighter. At least you will be armed with the rituals that will get you past the ‘devourer of souls’.

As we have observed in our brief encounter with Zoroastrianism, between the fifth and third centuries BCE, attitudes began to change. There was a problem that needed addressing! It seemed that the manner in which you lived your short and uncertain earthly life, had a serious impact on where you got to spend eternity. This concern changed everything!

I am aware that I have just glossed over two of the most significant centuries in the history of the classical world. Fifth century BCE Greece; the age of Pericles, the development of democracy, and theatre, created waves that still wash the world today. However, the fourth century BCE, which concluded with the takeover by Phillip of Macedonia and his famous son, Alexander was equally significant. During this war troubled century, both technology, and natural philosophy, underwent radical rethinking. xvi

t is the legacy of some of the great philosophers that has particular relevance to our current journey. Pythagoras may, or not, have existed, earlier, in in the sixth century BCE. His followers certainly did exist. They sought to study the laws of physics, particularly mathematics, viewing them as predictable and reliable aspects of the material world. However, they would not accept that the same laws could have any effect on the non-material world of the soul. They were also quite comfortable with the soul’s ability to “transmigrate” from one body to another body, even to that of an animal. They therefore upheld vegetarianism with the exclusion of beans. Apparently, beans might harbour souls. The Pythagoreans could tell this by the way beans caused ‘breath’ to leave the body from unexpected, and embarrassing orifices.

Plato took the concept further in the first years of the fourth century BCE, including transmigration of souls in his belief system. He perceived the soul to be seeking perfection, i.e. truth and beauty whilst trapped in a physical body that often preferred more animalistic pursuits. Later, in ‘The Republic’, he described the soul as being divided into the ‘irrational’, the animal soul, and the ‘rational’, which yearns for pure reason, He added the concept of ‘will’ to his perception of the soul. Humans could choose which aspect of the soul they would encourage.

Aristotle preferred the concept of one soul, one body. He said that souls could not exist without bodies, and that bodies could not have life without the immortal soul. What made human souls’ special was their ability to think rationally. Of course, this idea had ramifications for the afterlife. If you could only have one body, and hoped to have a soul and body reunion in a future world, then the body would need to be a fit housing for the immortal soul.

So far, I have willfully ignored the role and influence of the Epicurean philosophy. and similar skeptical individuals, such as Thales of Miletus. our present purpose is to follow the course of of polytheistic belief systems as they approach the white-water rapids of monotheism in the wake of our Immráma bound clerics. What is known of Epicurus, (341–270 BCE) is told in later commentaries, but Epicureans believed that the Gods, if Gods there were, had no interest in the human world and that death represented the final end of both body and soul. Epicurus taught that the goal of a tranquil life, free from pain and fear was best achieved through a self sufficient existence surrounded by friends. His influence remained popular, even into Roman times, and beyond, We will return to examine these less god-fearing attitudes in the second part of this article, ‘Otherworld’.

It was also around this time period that the plethora of ‘mystery’ religions from across the Persian / Hellenic world became more significant. At the heart of each of these cults was the idea of the transcendence of the individual soul. If you were a part of the group, knew the rituals, kept the practices, were ‘chosen’, then the chances of personal survival could be greatly enhanced. Exotic Egyptian beliefs became fashionable outside Egypt as they too, seemed to offer a method of personal survival. This is most likely why, as Jan Assman suggests, a canonical version of ‘The Book of the Dead’ developed at this late period of Pharaonic culture.

The Orphics characterised human souls as divine and immortal but doomed to live in a “grievous circle” of successive bodily lives through metempsychosis. If you were to practice an austere lifestyle you might develop a communion with the divine and eventually escape the tedious round of rebirths.

The ‘Eleusinian Mysteries’ were a very popular choice in the late Hellenic and Roman period. The cult may have originated in the Mycenaean bronze-age, but later, provided a route to personal divinity and, therefore, immortality. The rites were secret but written reports tell that the central, most holy, moment was the witnessing of an ear of corn reaped in silence.

In Roman times, the cult of Mithras was ubiquitous, particularly with soldiers. In the port of Ostia alone, twenty ‘Mithraeums’ were uncovered. The cult centred on the Persian hero Mithras, and offered personal redemption through identification with his killing of a sacred bull. Surprisingly, this bull-slaying is not a story from Persian mythology and the cult may have been an exotic Roman construct. Mithras’ celebrated birthdate was 25th December. It was a male only cult and this may have limited its eventual survival. His birthdate did, of course, survive.

By Roman times, the exotic cult of Isis became popular. The image of the sacred mother and her child were frequently found. As Christianity gained precedence, these images often became a model for the Mary carrying the child Jesus and many of the titles of the Egyptian mother figure came to be used for her.

Christianity, however it began was, in its early stages, effectively, a mystery cult, sharing elements in common with the Orphic and Eleusinian mysteries. Early images of Jesus found regularly in Roman catacombs show him in Orphic style, as a radiant young shepherd, surrounded by animals, rather than as a crucified man. [If the accompanying image is of Orpheus, it is one of many in the catacombs and seems to have been perfectly acceptable to early Christians. – Images from Christian catacombs could equally represent Orpheus or Christ.]

Zoroastrianism also continued its influence into early Christianity. Zarathushtra had prophesied saviours who would be born, or appear into the world to save its people in the coming days. Zoroastrianism also promised the resurrection of the body. So, some of the ideas that informed the new faith were not so unfamiliar.

This article began by evoking the Immráma voyagers and their journeys of exploration. Both monks and secular folk were setting out in a time of transition when a new belief system was gaining strength around them. However, before our weary monks re-appear through the mists, there are a couple of aspects of their world view that have, so far, been completely ignored. If we are to follow in the wake of our Immráma driven clerics, we must attempt catch a hold on a couple of the ‘sticky balls of wool’, that must have troubled our transitional travellers.

Our first sticky problem is “How and why did an underworld afterlife end up in the sky?” As we have seen, in early myth, the odd hero might get to become a constellation of stars, not a heap of fun, you might think. Egyptian pharaohs, could possibly expect a lift in the boat of the sun. Some, including Khufu, builder of the great pyramid, even packed their own boat in kit form.Whatever entitlement kings believed they had, ordinary people did not get to frolic among the stars. Neither did the gods, at least not in the pre Roman period. Gods lived wherever they felt most ‘at home’, near a well, by a river, in a forest, on a mountain, and so on. Gods of sun and moon might travel through the sky but even they needed a boat, or a chariot, excepting, perhaps, the Egyptian solar beetle Khepri, who rolled the sun through the sky like a piece of dung. Storm gods often operated from the heights of cloud topped mountains from where they could dispense lightning and thunder. They also favoured desert places. Even the Olympians, lived on Olympus, an inaccessible mountain.. There were other mountain abodes like Dikti in Crete where the baby Zeus, hidden from his enemies, was born annually.

But, as gods became distinct and increasingly separate from the Ancestor and Culture heroes, they were more likely to be found in locations not directly connected with their places of origin. They moved into impressive temples, especially designed for them by Nation States, Kings and Emperors. Eventually, selected Kings and Emperors, and occasionally their wives, even joined their august, celestial ranks.

.In many ways, the development of a celestial heaven was intuitive. As the underworld became associated with punishment, so reward was met with in a realm of light and air. The dualistic nature of in Zoroastrianism also had influence in the gradual distinction of chthonic and celestial worlds. The concept of airy angelic beings and demons of darkness was already present in this belief system which valued sunlight and truth. It is not clear where the ‘palace’ of Ahura Mazda was thought to be but the realm of the forces of Ahriman was located in the dark Underworld.

The Hebrew Scriptures which became the biblical Old Testament, may have been created in the light of Persian influence. This can certainly be identified in ‘The book of Enoch’. The text is a fascinating record from the fourth or third century BCE, and frequently references celestial beings. In book one, the ‘watchers’ clearly angels, become fallen and debased, punished, it seems, for offering humans forbidden skills which, not only include astral navigation, but also knowledge of root cuttings, and cosmetics. It then goes on to describe Enoch’s tour of the celestial realms (xvii)

The book is, most probably, a response to the post-exile, Judaic, world. For a people whose home had been destroyed, who had been uprooted and transferred to Babylon in the sixth century BCE, there was a need for a distinctive Jewish literature to support a recovering cultural identity. The Watchers, in the ‘Book of Enoch’ are similar, in essence, to the Anunnaki, a group of Mesopotamian beings who had originally gifted civilization to the earth.

However, Enoch’s celestial journey may well have been inspired by the newer Zoroastrian faith. Its ethical sense of personal responsibility, single ‘good’ creator, worshiped by heavenly beings must have been attractive to the Hebrew people, attuned to a more austere, increasingly monotheistic, cultural identity. The faith even promised the coming of a future messiah.

So to create a clear cultural distinction, the Jewish writers took familiar stories and made them recognisably their own. There is precedent for this process in the book of Genesis. Irving Finkel believes that a Jewish version of the flood narrative was written during the exile, rather than a couple of centuries later. In this version the world is destroyed by its creator because of wickedness, rather than just because human kind is becoming numerous and making too much noise.

By Roman times, divine beings are certainly located in a celestial realm. Virgil, in Aenid book VI, recounting his hero’s famous decent to the underworld, offers a traditional view, locating even the pleasant fields of Elysium there. However, he clearly refers to the gods as being ‘above’. Cicero, on the other hand, in the “Dream of Scipio” locates the abode of blessed souls among the stars. Heaven is now in the sky.

The second sticky issue is more troublesome. The monastic voyagers are most definitely monotheistic and seek to avoid non-Christian characters that Brain Mac Febul, and Maelduin openly encounter. How and when did the change to monotheism occur? Authors, a great deal more qualified than me, have undertaken full length books on this topic. There are no clear answers to this phenomena. However, I will include here, a couple of theories that have interested me.

Irving Finkel in a later chapter of “The Ark before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood” (xviii) discusses the position of a devout Jew exiled in Babylon. He poses a conversation between a Babylonian follower of Marduk and the Jewish worshiper of Yaweh. When the Babylonian discovers that the other worships a god who cannot be named, who may not be portrayed, has no family but yet demands total devotion, he fail to comprehend the attraction. However, as Finkel points out, Marduk, himself, was approaching the position of being a sole ruler. Finkel offers the translation of a cuneiform tablet from this period that makes it clear that all other gods are Marduk under his other aspects. The assyriologist also makes the point that if the Jewish exiles, had a god who was difficult to portray, then they needed to make him evident in their literature. This was an ideal opportunity to make him not only sovereign, (Thou shalt have no other gods before me), but solitary. (ixx)

Journalist, Robert Wright in his book, “The Evolution of God”, (xx) suggests that monotheistic thinking did not catch on until the third century BCE. This may well be It has often been suggested that Ankenaten, the so called heretic pharaoh who ruled around around1350 BCE was the first monotheist. However it is likely that Ankenaten wanted to be the sole mediator between the world and his preferred god, cutting the others out of the loop..

Wright points out that many nations preferred to absorb or adopt the gods of nations that they encountered through trade or conquest. It proved more effective. Your national god might be best but that did not mean others did not exist. However, the Jewish race had nothing to lose. They had become disposed and homeless. They were not in the position to be major traders or super conquerors. The scriptures regarding their god became a cultural reference point for them as a people. The written word held them together. The word of the ‘One God’ became a kind of identity forming cement.

In chapter of Jan Assmann’s ‘Cultural Memory and Early Civilization’ he poses the question as to why the religions of the book, i.e. Judaism, Islam and Christianity survived and grew in strength, when the literate beliefs of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, faded away. His answer is that, in these three religions, the god was effectively transferred, not to a temple but into a book. The deity became portable. Yes, God, Jehovah, Allah has special ‘Holy Places’ but his followers can follow his rites and rituals anywhere in the world. All that is required is the Holy Scriptures. Assman suggests that it is this fact, above all that supported the spread of the monotheistic, scripture based religions,

So, the stage is set, and we are almost at the point where we can make out the wash of the boat of the Ui Corra as they undertake their voyage of penitence.

Perhaps there is one more island blocking a clear view that we might just need to circumnavigate. This is the work of the early Christian fathers who helped to shape the world of our Monkish adventurers. There are a great number of shapers in this process but perhaps we can make for clear waters by commenting on only two.

The first of these left behind the earliest Christian literature in existence, mostly in the form of letters. This, is, of course Saul of Tarsus, Paul. He was said to have been a Pharisee in the early years of the first century who became a convert to the new beliefs. His letters to the Romans, the Corinthians, (one and two), the Galatians, Philippians, (one), the Thessalonians, and Philemon are generally accepted as authentic. The main effect he had on Christianity was to ‘mainstream it’. He was, after all, an educated man and a Jew. He helped to make the new practices more respectable, and under his influence it moved away from its original ‘mystery religion’ roots. His writings established that:

- Everyone was guilty of original sin, i.e. that all would be punished for Eve’s transgression.

- There would be a final day of Judgement

- All would be dammed unless redeemed by Jesus’ Baptism, i.e. just accepting membership of the group was not enough. Each would be judged on their own merits.

- Celibacy was to be encouraged

- The position of women was delimited.

St Augustine of Hippo, was equally influential in his time. (354CE to 430CE). Born in Algeria he was a highly educated man. At one point he held a prestigious position as a professor of rhetoric for the imperial court in Milan. In his youth he was a Manichean but became strongly influenced by Hellenistic philosophy, particularly Plato.

After his conversion, he adopted a severe monastic lifestyle, giving away all luxuries and selling his inheritance to establish a monastic foundation. He was ordained a priest in 391CE and made a bishop four years later.

He would not have disagreed with the attitudes of Paul of Tarsus but took the ramifications of original sin even further. He taught that all were dammed by Adam’s sin. God, in his mercy, might choose to save some souls, but certainly not all. A virtuous life would not save you if you were not one of ‘God’s Elect.’ This was the doctrine of pre-destination, demonstrated so graphically in the voyage of Brendan.

Towards the end of his life he strenuously opposed the so called, ‘Pelaganian heresy’. Pelagius asserted that God gave mankind a second chance, so that he might be rewarded by living a life of goodness. Augustine remained vehemently opposed to this view.

He also regarded women as being responsible for tempting men into sin. This did not improve their status within Christianity and may explain why Brendan’s ‘Land of Promise of the Saints’ was so empty and dull.

This long and convoluted Immrám, through some dark and speculative seas, may finally have reached calm water. We have caught up with the Uí Corra, encountering their hag ridden visions of Sunday Hells, and observed Brendan’s hotline acceptance of a God who can doom individuals to an eternity of torture merely because their fate is pre-determined to be so. These fanatically sincere voyagers are prepared to forgo human pleasures and to live hard and physically impoverished lives in order to hope for the promise of heaven.

The Uí Corra set out as penitents, seeking for forgiveness, in part, for their own birth. They achieve their stated goal but reach no wonderful ’Isles of Promise’. The marvels that they see, are visions of hellish punishment, vindicating their own world view. Brendan, is seeking news of an ‘Isle of Promise of the Saints’, a version of Eden, but without the serpent. Predictably, being Brendan, he finds it, but is not allowed to remain. His ‘Isle of Promise’, however, is a faint echo of the exotically populated island encountered by Bran, or Máel Dúin, and is certainly not an Isle of Women!

This section of the article ‘Underworld’ has plotted a course from early Neolithic times, (Çatalhöyük, Scara Brae) when it seems there was, an acceptance of death as a part of life and a willingness to keep active communication with the world of the ancestors. We have wandered through the dusty meaningless land of the shades towards the promise of salvation, in a new superior realm sharply divided from underworld place of punishment, for those who have correctly followed divinely prescribed practices. This is the route that has informed most of our monastic travelers.

But what about the others, the ones who went freely in search of a world of sinless health and pleasure, the Land of Apples or an Isle of Women?, The next section, ‘Otherworld’ will seek to plot an alternative course, one that may lead to the destinations of Bran, Máel Dúin and Tadhg.

End of part 1

Notes, references and bibliography

(i) Achilles tells his tale in homer’s Odyssey book XI http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Greek/Odyssey11.htm

(ii)The epic of Gilgamesh. A retelling by Stephen Mitchell. http://www.amazon.co.uk/Gilgamesh-Stephen-Mitchell-ebook/dp/B00IEDT51A/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1405198114&sr=1-2&keywords=gilgamesh

(iii) Akkadian: tablet 7 column 4

(iv) The Ugaritic story of Baal was deciphered from the famous alphabetic cuneiform tablets of Ras Shamra, uncovered in 1928. The story of Baal is less well known than his Egyptian counterpart, Osiris. Like the Egyptian god, he battles with his rival for his kingship. He also has a powerful sister ally, Annat who supports him with magic, and on occasion, with weapons. Later he battles with death (Mot). He is forced into death’s kingdom where he seems to die. His fierce sister goes down into the underworld and tears Mot to pieces. Baal is restored.

“She seized Mot by the edge of his garnent,

she grasped [him] by the end of his robe.

She lifted up her voice and cried:

‘Come Mot, give (me) my brother!’

But divine Mot replied:

‘What do you ask of me, O Virgin Anat?

I went out myself, and searched every mountain in the midst

Of the earth, every hill in the midst of the steppe.

My appetite felt the want of human beings,

My appetite the multitudes of the earth.

I reached “Paradise”, the land of pasture,

“Delight”, the steppe by the shore of death.

It was I who approached Valiant Baal:

It was I who offered him <like> a lamb in my mouth.

Like a kid in the opening of my maw.” Religious texts from Ugarit N. Wyatt

Baal, like Osiris, represents the regulation of water on the land to keep it fertile. His absence would bring drought. If he could not overcome Yam, his rival, the land might flood.

(v) “Temples Tombs and Hieroglyphs” by Barbara Mertz

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Temples-Tombs-Hieroglyphs-Popular-History/dp/0061252778

This is my favourite textbook on Egyptology although I would equally recommend

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt”

I am so sad that Barbara Mertz died last year. Under the name of “Elizabeth Peters”, she wrote her delightful series of Amelia Peabody books. I shall miss them.

(vi) The papyrus of Ani. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL14033599M/The_papyrus_of_Ani

(vii) From Cultural Memory and Early Civilization by Jan Assmann, Chapter 3A fascinating read, translated from the German and referenced by Klaus Schmitt in his writing on Gobekli Tepe.

(viii) Hesiod: Works and Days ff155

“But to the others father Zeus the son of Kronos gave a living and an abode apart from men, and made them dwell at the ends of earth. And they live untouched by sorrow in the Islands of the Blessed (Nesoi Makarôn) along the shore of deep swirling Okeanos, happy heroes for whom the grain-giving earth bears honey-sweet fruit flourishing thrice a year, far from the deathless gods, and Kronos rules over them; for the father of men and gods released him from his bonds. And these last equally have honour and glory.”

I find this and Homer’s reference to Menelaus’ eventual destination in the ‘Isles of the Blessed’ interesting. There is surely no direct connection, to the Irish tales, but the description has familiar echoes.

(ix) Try Vergil’s Aeneid, book six for an excellent description of Tarturus.

http://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/VirgilAeneidVI.htm

(x) Herodotus:The Histories (completed c. 440 BCE)

[from 1.131 abridged] …The customs which I know the Persians to observe are the following: they have no images of the gods, no temples nor altars, and consider the use of them a sign of folly. This comes, I think, from their not believing the gods to have the same nature with men, as the Greeks imagine. Their wont, however, is to ascend the summits of the loftiest mountains, and there to offer sacrifice to Zeus, which is the name they give to the whole circuit of the firmament. They likewise offer to the sun and moon, to the earth, to fire, to water, and to the winds…

To these gods the Persians offer sacrifice in the following manner: they raise no altar, light no fire, pour no libations; there is no sound of the flute, no putting on of chaplets, no consecrated barley-cake; but the man who wishes to sacrifice brings his victim to a spot of ground which is pure from pollution, and there calls upon the name of the god to whom he intends to offer The sacrificer is not allowed to pray for blessings on himself alone, but he prays for the welfare of the king, and of the whole Persian people, among whom he is of necessity included…

Of all the days in the year, the one which they celebrate most is their birthday. It is customary to have the board furnished on that day with an ampler supply than common. The richer Persians cause an ox, a horse, a camel, and an ass to be baked whole and so served up to them: the poorer classes use instead the smaller kinds of cattle. They eat little solid food but abundance of dessert, which is set on table a few dishes at a time; this it is which makes them say that “the Greeks, when they eat, leave off hungry, having nothing worth mention served up to them after the meats; whereas, if they had more put before them, they would not stop eating.” They are very fond of wine, and drink it in large quantities. To vomit or obey natural calls in the presence of another is forbidden among them. Such are their customs in these matters. It is also their general practice to deliberate upon affairs of weight when they are drunk; and then on the morrow, when they are sober, the decision to which they came the night before is put before them by the master of the house in which it was made; and if it is then approved of, they act on it; if not, they set it aside. Sometimes, however, they are sober at their first deliberation, but in this case they always reconsider the matter under the influence of wine…

Their sons are carefully instructed from their fifth to their twentieth year, in three things alone; to ride, to draw the bow, and to speak the truth. Until their fifth year they are not allowed to come into the sight of their father, but pass their lives with the women. This is done that, if the child die young, the father may not be afflicted by its loss. ..

They never defile a river with the secretions of their bodies, nor even wash their hands in one; nor will they allow others to do so, as they have a great reverence for rivers.”

See also http://www.ancient.eu/zoroaster/ for more on Zoroastrianism

(xi) http://gobeklitepe.info/ for more detail on this spectacular site:

http://arheologija.ff.uni-lj.si/documenta/authors37/37_21.pdf

(xii) A.W Reed offers several collection of Indigenous Australian stories

e.g. “Aboriginal Myths: Tales of the Dreamtime”, or “Aboriginal Myths, Legends and Fables”

(xiii) Çatalhöyük The Leopard’s Tale: Revealing the Mysteries of Turkey’s Ancient ‘Town by Ian Hodder

or go to the main website:

http://www.catalhoyuk.com/index.html

or to

http://alumni.stanford.edu/get/page/magazine/article/?article_id=69008for a very informative article on the history of Ian Hodder’s relationship with the site.

(xiv) Two lectures by Ian Hodder that are well worth watching: http://youtu.be/Bst5px48M4w (the leopard changes its spots) http://youtu.be/T-8miR3y294 Çatalhöyük Excavations & Its Impact on Cultural Heritage Road of Anatolia: Ian Hodder (Full Version)

(xv) Information on the spectacular excavations in Orkney. http://www.orkneyjar.com/archaeology/nessofbrodgar/

(xvi) I would highly recommend Michael Scott’s “From Democrats to Kings” which focuses specifically on Greece’s troubled fourth century BCE. His superb series on Greek theatre and democracy is also available on youtube.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/From-Democrats-Kings-Downfall-Alexander/dp/1848311311

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xf9cDKqwhQw (The Greatest Show on Earth)

(xvii)The book of Enoch. http://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/boe/

(xviii) The Ark before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood by Irving Finkel. (assistant curator of Assyriology at the British Museum)

I very highly recommend this book for readability, information and sheer enjoyment. This book is pure story archaeology.

(xix) Exodus 20

(xx) http://evolutionofgod.net/ “The Evolution of God” by Journalist, Robert Wright.

I have only dipped into this book but it has been well received by people sitting on several sides of the fence. (The mixed metaphor is intended.)