It wasn’t his fault. How could one so noble, so beautiful, have been at fault? He was the golden youth, the beloved one chosen by his mother’s people.

How could it all have gone so wrong?

How had his golden dreams become so tarnished?

He had grown up with his mother’s glowing stories.

“When you were conceived,” she had told him proudly, “your father prophesied your beauty. Every beautiful thing that is in Ireland, he had promised, both plain and fortress, ale and candle, woman, man and horse will be judged against you, so that people will say – that is a Bres!”

So he was special and his father must have been a king … but what king? In his growing, his mother would say no more. Bres knew he was destined to be a king himself.

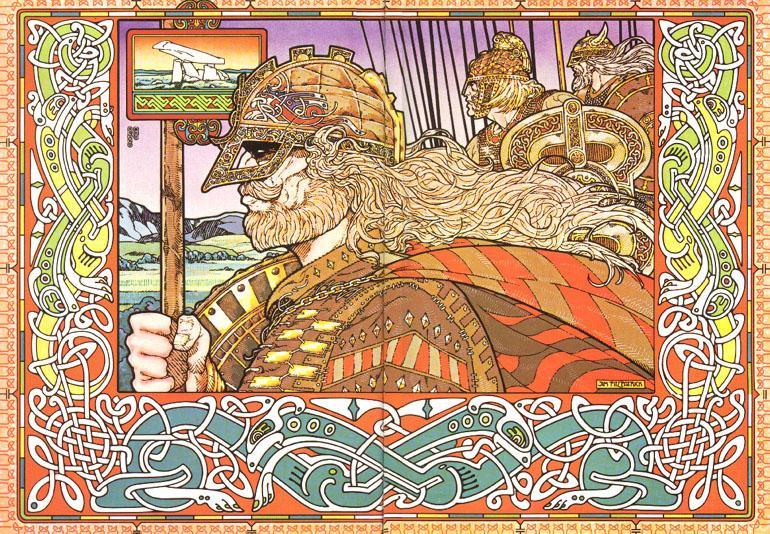

And it had come to be, just as he had foreseen, just as his unknown father had foreseen. For when Núada had been wounded in the great battle with the Fir Bolg, he could no longer stand as chief. It was certain that no blemished man could lead.

Yes, Dían Cécht, the great Dé Danann healer, had given Núada his magnificent silver hand, but that was still a blemish.

Bres had no blemish. Bres was the image of beautiful perfection.

He had every requisite for kingship. He deserved to be a king, and his finally – his mother’s people – had welcomed him as king.

His mother had given him land, and the Dagda, himself, had built him a great dún, fit for a chieftain.

No, he wasn’t to blame. He was Eochu Bres and he had gathered together a wealth of horses, a richness of cattle. And yet the golden abundance just seemed to flow away from between his fingers in tribute, paid to the enemies of his mother’s folk; the others, the Fomoire.

He was Bres the beautiful, and so the land should have become beautiful; but it was not.

In a time of dearth, all must work, even the warriors. And why shouldn’t that great oaf of a man, Ogma, collect wood? Why, they called Ogma “Sunnyface”, yet he was not so fair as Bres. And the Dagda?… If he was such a great builder, why should he not dig ditches?

They accused him of meanness. Him! Bres the beautiful!

They had spoken against him then, saying that under his rule, knives were not greased and their breaths did not smell of ale. They had tricked him into making false judgements.

It was not fair, was not just!

And finally, they had sent the poet Coirpre against him, and the poet had composed a sharp satire against the youth

“Without food on a dish,” he had spoken the words aloud

“Without the milk that feeds the growing calf

Without the shelter after dark

In a land where the poets and tellers of tales are unpaid

Bres’ prosperity no longer exists.”

And now, he, Bres, was as blemished as Núada had been; not in body, maybe, but in reputation, and that was the same.

So he had gone, complaining to his mother. It was not fair – and finally she had given him the ring that had belonged to his father, Elatha, and it fitted him well.

And so it was that he found his father’s kin, and he delighted in the knowledge that he was of the Fomoire, the enemies of the Dé Danann. Surely his own father would fight for him? Elatha had shaken his head, his face full of sadness. “If you lost your rule through injustice,” he had told him, “you cannot regain it with another injustice.”

And he had turned away. His father’s people would not follow him. Oh, they would come to battle with the Dé Danann before long, that was certain; but it would not be for his sake. He could fight for them, but they would never fight for him.

He was blemished forever.

And they had turned back to their plans, and called upon that ugly evil tempered giant of a man, Balor, with his poison eye, to be their champion.

And now the Fomoire host were in Ireland, and no more dreadful host ever came to the land, and Bres was with them, raging with anger and the injustice of his shattered dreams.

Oh, he would stand behind Balor and watch him destroy this new golden hero of his mother’s people; this Lug, who had taken his place. There was a story that this child, too, was half Fomorian like himself, but Bres did not care.

He would be there to see Lug suffer blemish and he, Bres, vowed to survive to see it.

I was formerly a Christian now a pagan. I have begun reading Lady Gregory’s book and Im shocked by apparent biblical parallels. The story of Bres is similar to the story of King Saul of the Iraelites. Saul’s story is 1000 bce but I was wondering the timing on the Bres story. In other words which came first? TIA