And the Morrigan spoke at last.

“The time will soon be upon us, and unrest will not pass us by. The leader of our people will be fatally blemished. Núada will be wounded in heart and hand. No longer will he hold golden prosperity within his grasp.”

The Dagda grinned.

“Dían Cécht will make him a hand of silver.”

“Silver will not be enough. The land will wither and die.”

And the Dagda answered her again, shaking his great head.

“The mountains may fall and the waters swallow the earth. Yet peace and plenty will return eventually.”

“Battle stands between us and that future. The fight will be long, fierce and bloody. We are one people, and yet we are two. We cannot share the Land forever with our own shadows. It will come to battle with the Fomoire.”

“Yet peace will come again.”

The Morrigan stood still, staring into the misty distance as if she could see soft shapes of coming times forming in the fretful wind. And then she spoke, sharply.

“We must prepare for the time of unrest. All, all must fall before the world can once more be set to rights. It must begin with the making of a new king, a child of chaos, a child born of both the Dé Dannan and the Fomoire, a child to weave our shadow-dance.”

The Morrigan paused a moment, frowning.

“Yet I see another such child who will pay the price for the shadow’s failings. It will not be fair.”

The Dagda laughed until his belly shook.

“It is never fair,” he answered her gently. “But it will be just. And best of all, we will play our own parts in this story. Yet it may be that we will not remember what we play until all is done.”

And so it began with a bargain between the Dé Danann and the Fomoire. Ériú, the daughter of Delbáeth, was given in marriage to Elatha, a prince of the Fomoire. But some said that the maiden did not know of the alliance, and first met with Elatha, unexpectedly, as she sat beside the calm ocean. She saw a great vessel of silver, and upon it a man of fairest appearance, clad in a cloak banded in gold. An hour of lovemaking they had, at his request and her willing granting, and he gave her his ring, telling her not to part with it except to someone whose finger it would fit.

Thus, the child Bres, the child named for chaos, was conceived and grew strong, nurtured by his mother’s people. And he was beautiful to see.

In time, the mists became firm and took shape. It all happened as the Morrigan had foreseen. When Núada lost his hand in a fight with Sreng, champion of the Fir Bolg, Núada could no longer lead his people, and the young Bres was chosen as king, not least for his great beauty. But his golden brightness cast all else into shadow. Bres took the cows of Ireland and their milk to himself until the land was squeezed dry. He forced the Dé Danann to menial work, starving them of food. Even the Dagda dragged dead wood, weakened by hunger. The land withered.

The Mac Óc, son of the Dagda, watched his troubled father, shaking his head.

“You forget that you do not have to put up with this,” he laughed. “Let me give you my advice. As payment for your work, ask Bres for the black-maned, spirited heifer, and nothing more, but do not take payment yet.”

“Why?” asked his father.

“Hunger has eaten your memory. Wait, and you will know.”

The Mac Óc also told him how to trick the satirist, Cridenbél, who was demanding the three best parts of his father’s food each evening.

“Take these gold coins and hide them in the food,” he grinned. “If Cridenbél swallows them, he will have had the best of what you have to offer, but it will do him no good. He will die. Even if you are accused of his murder, it will favour our cause. When Bres orders your death, as he may, you will prove your innocence when the satirist is cut open and they discover the gold. You gave him the best you had, and he died of it.”

And so it came to be that the Dagda’s trick caused the shadow-king to give a bad judgement. Then the poet, Coirpre, laughed and made a satire on Bres that would be a blemish on his good name for all time.

Without food quickly on a dish,

Without cow’s milk on which a calf grows,

Without a man’s habitation after darkness remains,

Without paying a company of storytellers — let that be Bres’ condition.

Bres, no longer king, fled back to his father’s people. The shadows and the hunger fled with him and, for a while, the land was untroubled. In that bright time, Míach, the son of Dían Cécht the craftsman, healed Núada, restoring to him a hand of flesh. And, although Miach was himself cut down as a result of the deed, even his death re-seeded the land with hope for the future.

In this bright brief time, while the land still breathed, the Dagda called to himself allies of power, those who knew the secrets of water, fire, air and earth; and they secluded themselves in secret at Grellach Dollaid. “For in the battle to come,” the Dagda told them, “all may change. We must be prepared to raise the mountains to crumbled dust and hide the waters of the land that our enemies will find no comfort here.” And for a year they prepared their arts.

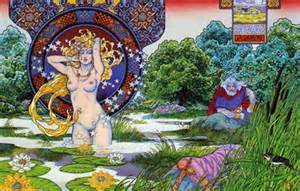

The sun rippled the quick water of the stream into flowing rivulets of silver. The woman’s eyes relaxed, and, almost gently, she unwound her red gold hair and let it flow, unbound, into nine tresses, river-bright. She sighed deeply, it was almost a laugh, and playfully, she straddled the little stream, seeing the sparkling flood idle between her feet.

The man watched her, a soft light of familiar longing in his deep earth eyes. He waited while the woman knelt to wash in the fresh water of the stream flow. This was his woman. This was the Morrigan.

They came together in contentment in this place, their place, the Bed of the Couple it was called. Yes, this was a bright time, a time between times, when the land waited, held at the balance point.

“This is the time,” said the woman finally, staring into the star-point stream ripples. “Now we go down into battle and destruction. The Fomoire, our enemy, are very close. You must summon our people to this ford. The balance has tipped.”

And she left, saying that she would go to find Indéch, leader of the Fomoire, and seek a way to weaken him.

The Dagda stood until she was out of sight, his eyes twinkling. He had no intention of waiting here. When he was sure she was gone, he set off for the Fomoire camp himself. No secret spying here, he walked straight in, demanding a truce. The Fomoire eyed him with suspicion, unsure of his intentions.

“He is a man of quicksilver wit and wise words,” they whispered. “He will accuse us of niggardliness as his people did with Bres.”

And so they offered him impossible hospitality. The king’s cauldron, five fists deep, was filled with eighty gallons of new milk, meal and fat. Entire goats, sheep and pigs were added, and boiled with the porridge. With great relish, they poured the whole lot into a hole in the ground and bade him to eat his fill. Oh, there was no way that they would lay themselves open to satire on his account!.

They watched in fascinated horror while the Dagda ate every bit using the man-size ladle. Ate every scrap, he did, even picking out the last morsels with his finger.

And then he set off, a figure of fun, but not caring that his rough tunic failed to cover his naked buttocks, or that his distended belly dragged almost to the ground. Oh no. He was waiting for the next adventure and it wasn’t long coming.

Maybe Indéch’s daughter was sent to offer him a further hospitality that he was in no shape to accept, and maybe it was her own idea. Either way, she flaunted herself before him, taunting him, jumping on his back and knocking him to the ground.

“Ah come on, you great lump of a man,” she teased. “Carry me on your back to my father’s house.”

“Can’t do that,” he replied, enjoying the game. “It is geis for me to carry anyone who cannot say my full name.” Now the Dagda had a whole host of names, too many to remember easily, but she could recall every one after he had spoken them once. Laughing she threw herself onto his belly, ridding him of the encumbering contents. She climbed on his back. Before long, wordplay led to fore-play and an unexpected alliance with the daughter of the enemy king.

But the brief bright time was over and the breathing of the land grew shallow again. The prosperity of the land, the Glas Gabann, that black-maned, spirited heifer. won by the Dagda in lawful trickery, still remained in the hands of the Fomoire. Without her, the land would parch and die.

For her sake, battle was enjoined.

At first, it seemed that all went well for the Dé Danann. Goibniu’s skills of fire-craft and metal offered matchless, ever-sharp weapons, and Dían Cécht’s skills of water-craft and healing created a well capable of reviving any wounded man.

Ruadán was unhappy. He was the son of a king, but he felt ignored, unimportant. Bres, Ruadán’s father, had fled back to the Fomoire in disgrace, but he, the son, had committed no unworthy act. He had no great deeds to his name, but If it came to it, he had been given no opportunity to show his worth. Then an idea brightened his heart. He would be a spy. He would enter the enemy camp and uncover their secrets. It would be easy for him, of course, for his mother, Brig, was Dé Danann.

And it worked. The Dé Danann saw only Brig’s son. No-one saw the efficient spy. He discovered the healing well and proudly reported his findings. In the darkness, the battle-leader, Octrilach, gathered his men and heaped stones high over the pool, destroying it’s virtue.

Ruadán was delighted, He would win great renown as a spy.

In the ruddy forge, Goibniu was occupied creating his marvellous spear-heads. The firelight leaped, lighting flame in Ruadán’s own red hair.

“What is it you want, Brig’s son?” asked Goibniu amiably. Ruadán begged to hold a spear, but once the smooth shaft was in his hand, he aimed at Goibniu and threw. The spear pierced the smith cleanly. Here was Ruadán’s chance to help his father’s people. With a frown, Goibniu pulled the spear from his body and, almost casually, threw it back. The boy fell.

Only Brig mourned, keening wildly. But then, it was her son who had caused the healing well to be destroyed. He would not be revived And so, the boy who should have been a leader, should have been a hero, died without renown.

But now the battle raged in earnest. It is said, and with authority that;

Many beautiful men fell there in the stall of death. Great was the slaughter and the grave-lying which took place there. Pride and shame were there side by side. Harsh too the tumult all over the battlefield — the shouting of the warriors and the clashing of bright shields, the swish of swords and ivory-hilted blades, the clatter and rattling of the quivers, the hum and whirr of spears and javelins, the crashing strokes of weapons.

Yet, at the end, the Fomoire were utterly defeated and driven to the sea, never to be a threat to the land again. There were offers and negotiations and peace treaties accepted. There was the counting of the slain and the recounting of deeds. The battle was over.

But the land was not yet restored, the natural order not yet re-established. Together, the Dagda and the Morrigan had one more great task to undertake. The Dagda followed the fleeing Fomoire until he came to the feasting hall where sat Elatha and his son, Bres. And there, safe on the wall, hung the Dagda’s own harp.

Gladly he called it with the words;

Come summer, come winter,

Mouths of harps and bags and pipes!

And gladly the harp leapt into his hands. Straightway he played for them, whether they would or no, the three great musics; the joyful, the sorrowful, and thirdly the music that made all present sleep deeply. And as he returned to the land of the Dé Dannann, the Glas Gabann followed the Dagda Mór, and her lowing called all the cows of Ireland to follow behind.

As she walked, green grass grew up under her hooves, and the land breathed green again, fresh and growing.

The Morrigan spread her arms and spoke a poem of peace and prosperity.

“The land lies, a cup of honeyed strength, a strength for all

Here there will be a forest-point of field-fences

The horn-counting of many cows

And the encircling of many fields

There will be sheltering trees

So fodderful of beech mast that the trees themselves will be weary with the weight.

In this land will come abundance bringing

Wealth for our children…

But not forever

The battle is not over forever.

The land will fail, and justice will fall. The rhythm of your harp will not keep us safe forever.”

“But all is ordered for now,” answered the Dagda.

“Let us enjoy good food, good beer and good company, while we may.”

The Glas Gabann lowed softly in the green grassed enclosure.

Notes on the story

This re-telling of the story of Moytura is, of course, pure speculation, a fabrication constructed from our explorations of the earliest story-shards, as discussed in the podcast episode.

It is also a modern re-telling. Like the medieval or the eighteenth and nineteenth century versions of Irish stories, every re-telling is a re-interpretation reflecting the values and attitudes current in the period. I am very much aware that this version reveals the delight taken by both myself and Isolde in the tales of the Dagda and the role of the Morrigan.

So what happens when the Shiny Young Hero, Lugh, is no longer present?. We would argue, perhaps, that the story takes on a deeper, more earthy quality. It could be regarded as being thematically more primitive, concerning itself with the creation of order in the living land rather than placing the exploits of heroic individuals at its centre.

And yet, I find myself almost missing that brash, overconfident, young figure, our Jack-the-Lad giant-killer. He has certainly swash-buckled his way into our affections and into virtually every action film or show you might be likely to watch on television. You can’t keep him out for long!

You can almost hear the Dagda laughing!

April ’13