In the podcast episode on “The Four Craftsmen”, we discussed the manner in which characters found only within the saga of Moytura developed an enduring popularity in folklore and story. This would seem to have particular relevance in the case of Goibniu the Dé Danann smith.

In the podcast episode on “The Four Craftsmen”, we discussed the manner in which characters found only within the saga of Moytura developed an enduring popularity in folklore and story. This would seem to have particular relevance in the case of Goibniu the Dé Danann smith.

Goibniu is certainly connected, if not cognate, with the Gobbán Sáor (Gobban Saer / Gobhaun Saor) and his stories; although there are differences.

The Gobbán Sáor is known as a builder and architect, rather than, specifically, as a smith. In popular folklore he becomes known as St Gobban the builder. The Catholic Encyclopedia regards him as historical, born at Turvey, near Malahide, about 560 CE.

Texts exist that have him aiding various saints in building churches, including an eighth-century poem, “The Life of St Abban”.

The stories are now best known in the lively collection of stories by Ella Young entitled “The Wonder Smith and His Son”, published in 1927. They are available on-line, but I have included a couple of the tales below. They are clearly derived from the Moytura tales. Balor is present along with the terrible Fomorians from the Land Under Wave and Aengus still helps his father, the Dagda, find a way to trick Crídenbél by feeding him gold.

But in these stories, the wisdom and quick-witted trickery of the Dagda and Aengus is handed on to the Smith and his son. And finally, Goibniu has been remembered down the centuries, not perhaps for his magical weapons or his marvellous skill in crafting, but for his sharp wits and brave luck.

As a storyteller, I know that, whereas battles and heroic deeds are memorable, the most enduring and best-loved tales must have a decent helping of that good-natured wit typified by the exploits of the Dagda and Aengus, here shared by Goibniu. For, in the words of the wife of the Wondersmith’s son, “…sure everyone knows that storytelling is the way to shorten the road”.

How the Son of The Gobhaun Saor Sold the Sheepskin

THE GOBHAUN SAOR was a great person in the old days, and he looked to his son to be a credit to him. He had only one son, and thought the world and all of him, but that was nothing to what the son thought of himself. He was growing up every day, and the more he grew up the more he thought of himself, till at last the Gobhaun Saor’s house was too small to hold him, and the Gobhaun said it was time for him to go out and seek his fortune. He gave him a sheepskin and his blessing, and said:

“Take this sheepskin and go into the fair and let me see what cleverness you have in selling it.”

“I’ll do that,” said the son, “and bring you the best price to be got in the fair.”

“That’s little,” said the Gobhaun Saor, “but if you were to bring me the skin and the price of it, I’d say you had cleverness.”

“Then that’s what I’ll bring you!” said the son, and he set off on his travels.

“What do you want for that sheepskin you have?” said the first man he met in the fair. He named his price.

“‘Tis a good price,” said the man, “but the skin is good, and I have no time for bargaining; here is the money; give me the skin.”

“I can’t agree to that,” said the son of the Gobhaun Saor. “I must have the skin and the price of it too.”

“I hope you may get it!” said the man, and he went away laughing. That was the way with all the men that tried to buy the skin, and at last the son of the Gobhaun Saor was tired of trying to sell it, and when he saw a crowd of people standing around a beggar man he went and stood with the rest. The beggar man was doing tricks and every one was watching him. After a while he called out:

“Lend me that sheepskin of yours and I’ll show you a trick with it! ”

“You needn’t ask for the loan of that skin,” said one of the men standing by, “for the owner of it wants to keep it and sell it at the same time, there’s so much cleverness in him!”

The son of the Gobhaun Saor was angry when that was said, and he flung down the skin to the juggler-man.

“Do a trick with it if you can,” said he.

The beggar man spread out the skin and blew between the wool of it, and a great wood sprang up–miles and miles of a dark wood–and there were trees in it with golden apples. The people were frightened when they saw it, but the beggar man walked into the wood till the trees hid him. There was sorrow on the son of the Gobhaun Saor at that.

“Now I’ll never give my father either the skin or the price of it,” he said to himself, “but the least I may do is to take him an apple off the trees.” He put out his hand to an apple, and when he touched it he had only a bit of wool in his hand. The sheepskin was before him. He took it up and went out of the fair.

He was walking along the roads then and it was growing dark and he was feeling sorry for himself, when he saw the light of a house. He went toward it, and when he came to it the door was open, and in the little room inside he saw the beggar man of the fair and another man stirring a big pot.

“Come in,” said the beggar man; “this is the house of the Dagda Mor, the World Builder. It isn’t much, as you see, but you may rest here and welcome, and maybe the Dagda will give us supper.”

“Son Angus,” said the Dagda to the beggar man, “you talk as if I had the Cauldron of Plenty, and you know well that it is gone from me. The Fomorians have it now and I have only this pot. Hard enough it is to fill it, and when it is filled I never get a good meal out of it, for a great, hulking, splay-footed churl of a Fomorian comes in when he smells the meat and takes all the best of it from me, and I have only what remains when he has gorged himself; so I am always hungry, son Angus.”

“Your case is hard,” said Angus, “but I know how you can help yourself.”

“Tell me how,” said the Dagda.

“Well,” said Angus, “get a piece of gold and put it into the best part of the meat, and when the Fomorian has eaten it up tell him he has swallowed the gold; his heart will burst when he hears that, and you’ll be rid of him.”

“Your plan is good,” said the Dagda, “but where am I to get the gold? The Fomorians keep me building all day for them, but they give me nothing.”

“I wish I had a piece of gold to give you myself,” said Angus. ” ‘Tis a bad thing to be a beggar man! The next time I disguise myself I’ll be a prince.” He laughed at that, but the Dagda stirred the pot and looked gloomy. The son of the Gobhaun Saor felt sorry for him and remembered that he had a gold ring his father had given him. He pulled it off his finger and gave it to the Dagda.

“Here,” said he, “is a piece of gold and you can be rid of the Fomorian.”

The Dagda thanked him and gave him his blessing and they spent the night in peace and happiness till morning reddened the sky.

When the son of the Gobhaun Saor started to go, Angus set him a bit on the way.

“You are free-handed,” he said to him, “and a credit to your father, and now I’ll give you a bit of advice–Say ‘Good morrow kindly’ to the first woman you can meet on the road, and good luck be with you.”

It wasn’t long till the son of the Gobhaun Saor saw a woman at a little stream washing clothes. “Good luck to the work,” he said, “and good morrow kindly.”

“Good morrow to yourself,” said she, “and may your load be light.”

“It would need to be light,” said he, “for I’ll have far enough to carry it.”

“Why so? ” said she.

“I must carry it till I meet some one to give me the price of it and the skin as well.”

“You need travel no further for that,” said she; “give me the sheepskin.”

“With a heart and a half,” said he, and he gave her the skin. She paid the price, and she plucked the wool from the skin and threw him the skin.

“Now you can go home to your father,” she said.

He wasn’t long going, and he was proud when he gave the Gobhaun the skin and the price of it.

“What man showed you the wise way out of it?” said the Gobhaun Saor.

“No man at all,” said the son, “but a woman.”

“And you met a woman like that, and hadn’t the wit to bring her with you!” said the Gobhaun Saor. “Away with you now, and don’t let the wind that is behind you come up with you. till you ask her to marry you!”

The son didn’t need the second word, and the wind didn’t overtake him till he asked the woman to marry him. They came back together, and the Gobhaun made a wedding feast for them that was remembered year in and year out for a hundred years.

How the Son of The Gobhaun Saor Shortened the Road

ONE day the Son of the Gobhaun Saor was sitting outside in the sunshine, cutting a little reed into a pipe to make music with. He was so busy that he never saw three stranger-men coming till they were close to him. He looked up then and saw three thrawn-faced churls wrapped in long cloaks. “Good morrow to you,” said the Son of the Gobhaun Saor. “Good morrow,” said they. “We have come to say a word to the Son of the Gobhaun Saor.” “He is before you,” said the Son. “We have come,” said the most thrawn-faced of the three, “from the King of the Land Under Wave to ask you to help him; he has a piece of work that none of his own people can do, and you have the cleverness of the Three Worlds in your fingers.” “‘Tis my father has that,” said the Son of the Gobhaun Saor. “Well,” said the other, “bring your father with you to the Land Under Wave and your fortune’ made.”

The Son of the Gobhaun Saor set off at that to find his father. “I have the news of the world for you and your share of fortune out of it,” he said. “What news? ” said the Gobhaun. “The King of the Land Under Wave has sent for me; if you come with me your fortune is made.” “Did he send you a token?” “No token at all, but do you think I would not know his messengers? ” “O, ’tis you has the cleverness!” said the Gobhaun Saor.

They set out next morning, and as they were going along, the Gobhaun Saor said: “Son, shorten the way for me.” “How could I do that?” said the Son, “if your own two feet can’t shorten it.” “Now, do you think,” said the father, “that you’ll make my fortune and your own too when you can’t do a little thing like that!” and he went back to the house.

The Son sat down on a stone with his head on his hands to think how he could shorten the road, but the more he thought of it the harder it seemed, and after a while he gave up thinking and began to look round him. He saw a wide stretch of green grass and an old man spreading out locks of wool on it. The old man was frail and bent, and he moved slowly spreading out the wool. The Son of the Gobhaun Saor thought it hard to see the old man working, and went to help him, but when he came nearer a little wind caught the wool and it lifted and drifted, and he saw it wasn’t wool at all but white foam of the sea. The old man straightened himself, and the Son of the Gobhaun Saor knew it was Mananaun the Sea-God, and he stood with his eyes on the sea-foam and had nothing to say. “You came to help me,” said Mananaun. “I did,” said the Son of the Gobhaun Saor, “but you need no help from me.” “The outstretched hand,” said Mananaun, “is the hand that is filled the fullest; stoop now and take a lock of my wool, it will help you when you need help.” The Son of the Gobhaun Saor stooped to the sea-foam; the wind was blowing it, and under the foam he saw the blue of the sea clear as crystal, and under that a field of red flowers bending with the wind. He took a handful of foam. It became a lock of wool, and when he raised himself Mananaun was gone, and there was nothing before him but the greenness of grass and the sun shining on it.

He went home then and showed the lock of wool to his wife and told her the sorrow he was in because he couldn’t shorten the road for his father. “Don’t be in sorrow for that,” said she, “sure everyone knows that storytelling is the way to shorten a road.” “May wisdom grow with you like the tree that has the nuts of knowledge!” said he. “I’ll take your advice, and maybe to-morrow my father won’t turn back on the road.”

They set out next day and the Gobhaun Saor said–” Son, be shortening the road.” At that the Son began the story of Angus Oge and how he won a house for himself from the Dagda Mor: it was a long story, and he made it last till they came to the White Strand.

When they got there they saw a clumsy ill-made boat waiting for them, with ugly dark-looking men to row it.

“Since when,” said the Gobhaun Saor, “did the King of the Land Under Wave get Fomorians to be his rowers, and when did he borrow a boat from them?” The Son had no word to answer him, but the ugliest of the ill-made lot came up to them with two cloaks in his hand that shone like the sea when the Sun strikes lights out of it. “These cloaks,” said he, “are from the Land Under Wave; put one about your head, Gobhaun Saor, and you won’t think the boat ugly or the journey long.” “What did I tell you? ” said the Son when he saw the cloaks. “You have your own asking of a token, and if you turn back now in spite of the way I shortened the road for you, I’ll go myself and I’ll have luck with me.” “I’ll go with you,” said the Gobhaun Saor; he took the cloaks and they stepped into the boat. He put one round his head the way he wouldn’t see the ugly oarsmen, and the Son took the other.

As they were coming near land the Gobhaun Saor looked out from the cloak, and when he saw the place he pulled the cloak from his Son’s head and said: “Look at the land we are coming to.” It was a dark, dreary, death-looking country without grass or trees or sun in the sky. “I’m thinking it won’t take long to spend the fortune you’ll make here,” said the Gobhaun Saor, “for this is not the Land Under Wave but the country of Balor of the Evil Eye, the King of the Fomorians.” He stood up then and called to the chief of the oarsmen: “You trapped us with lies and with cloaks stolen from the Land Under Wave, but you’ll trap no one else with the cloaks,” and he flung them into the sea. They sank at once as if hands pulled them down. “Let them go back to their owners,” said the Gobhaun Saor.

The Fomorians ground their teeth and cursed with rage, but they were afraid to touch the Gobhaun or his Son because Balor wanted them; so they guarded them carefully and brought them to the King. He was a big mis-shapen giant with a terrible eye that blasted everything, and he lived in a great dun made of glass as smooth and cold as ice. “You are a fire-smith and a wonder-smith, and your Son is a wise man,” he said to the Gobhaun. “I have brought the two of you here to put fire under a pot for me.” “That is no hard task,” said the Gobhaun. “Show me the pot.” “I will,” said Balor, and he brought them to a walled-in place that was guarded all round by warriors. Inside was the largest pot the Gobhaun Saor had ever laid eyes on; it was made of red bronze riveted together, and it shone like the Sun. “I want you to light a fire under that pot,” said Balor.” “None of my own people can light a fire under it, and every fire over which it is hung goes out. Your choice of good fortune to you if you put fire under the pot, and clouds of misfortune to you if you fail, for then neither yourself nor your Son will leave the place alive.”

“Let everyone go out of the enclosure but my Son and myself,” said the Gobhaun Saor, “until we see what power we have.” They went Out, and when the Gobhaun Saor got the place to himself he said to the Son: “Go round the pot from East to West, and I will go round from West to East, and see what wisdom comes to us.” They went round nine times, and then the Gobhaun Saor said: “Son, what wisdom came to you?” “I think,” said the Son, “this pot belongs to the Dagda Mor.” “There is truth on your tongue,” said the Gobhaun, “for it is the Cauldron of Plenty that used to feed all the men of Ireland at one time, when the Dagda had it, and everyone got out of it the food he liked best. It was by stealth and treachery the Fomorians got it, and that is why they cannot put fire under it.” With that he let a shout to the Fomorians: “Come in now, for I have wisdom on me.” “Are you going to light the fire,” said the Son, “for the robbers that have destroyed Ireland?” “Whist,” said the Gobhaun Saor; “who said I was going to light the fire? ” “Tell Balor,” he said to the Fomorians that came running in, “that I must have nine kinds of wood freshly gathered to put under the pot and two stones to strike fire from. Get me boughs of the oak, boughs of the ash, boughs of the pine tree, boughs of the quicken, boughs of the blackthorn, boughs of the hazel, boughs of the yew, boughs of the whitethorn, and a branch of bog myrtle; and bring me a white stone from the door step of a Brugh-fer, and a black stone from the door step of a poet that has the nine golden songs, and I will put fire under the pot.”

They ran to Balor with the news, and he grew black with rage when he heard it. “Where am I to get boughs of the oak, boughs of the ash, boughs of the pine tree, boughs of the quicken, boughs of the blackthorn, boughs of the hazel, boughs of the yew, boughs of the white-thorn and a branch of bog myrtle in a country as barren as the grave? ” said he. “What poet of mine knows any songs that are not satires or maledictions, and what Brugh-fer have I who never gave a meal’s meat to a stranger all my life? Let him tell us,” said Balor, “how the things are to be got?” They went back to the Gobhaun Saor then and asked how the things were to be got. ” It is hard,” said the Gobhaun, “to do anything in a country like this, but since you have none of the things, you must go to the Land of the De Danaans for them. Let Balor’s Son and his Sister’s Son go to my house in Ireland and ask the woman of the house for the things.”

Balor’s Son set out and the Son of Balor’s Sister with him. Balor’s Druids sent a wind behind them that swept them into the country of the De Danaans like a blast of winter. They came to the house of the Gobhaun Saor, and the wife of the Son came out to them. “O Woman of the House,” said they, “we have a message from the Gobhaun Saor.” He is to light a fire for Balor, and he sent us to ask you for boughs of the oak, boughs of the ash, boughs of the pine tree, boughs of the quicken, boughs of the blackthorn, boughs of the hazel, boughs of the yew, boughs of the whitethorn and a branch of bog myrtle. “You are to give us,” he said, “a white stone from the door step of a Brugh-fer, and a black stone from the door step of a poet that has the nine golden songs.”

“A good asking,” said the woman, “and welcome before you!” “Let the Son of Balor come into the secret chamber of the house.” He came in, and she said: “Show me the token my man gave you.” Now, Balor’s Son had no token, but he wouldn’t own to that, so he brought out a ring and said: “Here is the token.” The woman took it in her hand, and when she touched it she knew that it belonged to Balor’s Son, and she went out of the room from him and locked the door on him with seven locks that no one could open but herself.

She went to the other Fomorian then and said: ” Go to Balor and tell him I have his Son, and he will not get him back till I get back the two that went from me, and if he wants the things you ask for he must send a token from my own people before I give them.”

Balor was neither to hold nor to bind when he got this news. “Man for man,” he said; “she kept one and she’ll get back one, but I’ll have my will of the other. The Gobhaun Saor will pay dear for sending my Son on a fool’s errand.” He called to his warriors and said:

“Shut the Gobhaun Saor and his Son in my strongest dun and guard it well through the night. To-morrow I’ll send the Son to Ireland and get back my own Son, and to-morrow I’ll have the blood of the Gobhaun Saor.”

The Gobhaun Saor and his Son were left in the dun without light, without food, and without companions. Outside they could hear the heavy-footed Fomorians, and the night seemed long to them. “My sorrow,” said the Son, “that ever I brought you here to seek a fortune, but put a good thought on me now, father, for we have come to the end of it all.” ” I needn’t blame your wit,” said the father, “that had as little myself. Why did I send only two messengers? Why didn’t I send a lucky number like three? Then she could have kept two and send one back. Troth, from this out every fool will know there’s luck in odd numbers!”

“If we had light itself,” said the Son, “it wouldn’t be so hard, or if I had a little pipe to play a tune on.” He thought of the little reed pipe he was making the day the three Fomorians came to him, and he began to search in the folds of his belt for it. His hand came on the lock of wool he got from Mananaun, arid he drew it out. “O the fool that I was,” he said, “not to think of this sooner! ” “What have you there? “said the Gobhaun. “I have a lock of wool from the Sea-God, and it will help me now when I need help.” He drew it through his fingers and said: “Give me light!” and all the dun was full of light. He divided the wool into two parts and said: “Be cloaks of darkness and invisibility!” and he had two cloaks in his hand coloured like the sea where the shadow is deepest. “Put one about you,” he said to the Gobhaun, and he drew the other round himself. They went to the door, it flew open before them, a sleep of enchantment came on the guards and they went out free. “Now,” said the Son of the Gobhaun Saor, “let a small light go before us; and a small light went before them on the road, for there were no stars in Balor’s sky. When they came to the Dark Strand the Son struck the waters with his cloak and a boat came to him. It had neither oars nor sails; it was pure crystal, and it was shining like the big white star that is in the sky before sunrise. “It is the Ocean-Sweeper,” said the Gobhaun. “Mananaun has sent us his own boat! ” ” My thousand welcomes before it,” said the Son, “and good fortune and honour to Mananaun while there is one wave to run after another in the sea! ”

They stepped into the boat, and no sooner had they stepped into it than they were at the White Strand, for the Ocean-Sweeper goes as fast as a thought goes, and takes the people she carries at once to the place they have their hearts on.

It is a good sight our own land is! “said the Gobhaun when his feet touched Ireland. “It is,” said the Son, “and may we live long to see it!” There was no stopping after that till they reached the house of the Gobhaun, and right glad was the Woman of the House to see them. They told her all their story, and she told them how she had seven locks on Balor’s Son. “Let him out now,” said the Gobhaun, “and ask the men of Ireland to a feast and let the Fomorian take back a good account of the treatment he got.”

Well, there was the feast of the world that night. The biggest pot in the Gobhaun’s house was hung up, and the Gobhaun himself put fire under it. He took boughs of the oak, boughs of the ash, boughs of the pine tree, boughs of the quicken, boughs of the blackthorn, boughs of the hazel, boughs of the yew, boughs of the whitethorn, and a branch of bog-myrtle. He got a white stone from the door-step of a Brugh-fer, and a black stone from the door-step of a poet that had nine golden songs. He struck fire from the stones and the flames leaped up under the pot, red blue and scarlet and every colour of the rainbow.

It is not dark or silent Gobhaun’s house was that night, and if all the champions on the golden crested ridge of the world had come into it with the hunger of seven years on them they could have lost it without trouble at Gobhaun’s feast.

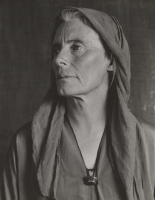

Ella Young (December 26, 1867 – July 23, 1956) was an Irish poet and mythologist active in the Celtic Revival literary movement of the late 19th and early 20th century. Born in Ireland, Ella Young was an author of poetry and children’s books. She emigrated from Ireland to the United States in 1925. Ella Young held a chair in Irish Myth and Lore at the University of Berkeley for seven years.

2 thoughts on “Goibniu and the Gobbán Sáor”