The Colloquy of Colmcille and the Youth at Carn Eolairg

As it might have been reported by the most insignificant and junior of the sainted man’s monks

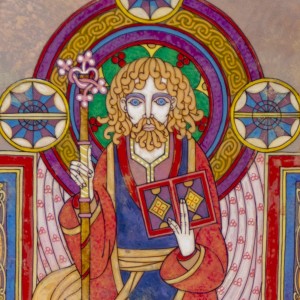

Some say it was Mongán, son of Fiachna, who spoke to Colmcille that Thursday morning. They had conversed all day, they had – and all night too. Some of the brothers, aggrieved by this sudden loss of guidance, had agreed to keep a watchful vigil on the curious behaviour of their master. It had been a sleepy vigil for most, but not for the youngest of them. Murmuring voices under a chilly moon had kept him from sleep. Now in the yellow dawn the rim of a misty sun had lifted above the mother-of-pearl horizon. The beautiful youth still stood, haloed against the dawn, his long hair flowing with the dawn breeze. His face and his figure was in shadow. It was strange, thought the young brother, that this mysterious visitor was somehow always in shadow. A leafy bough-shade, a sudden wisp of sea mist, the low dazzle of evening light; not once had he seen the stranger clearly – not once. And when had the youth arrived, here at dawn on the border of the great sea-lough? No one had seen his coming. And if this was the young princeling Mongán, son of Fiachna, then where was his retinue? Why had he come alone? But there were whispers about this youth – whispers of prophecy, whispers of destiny, whispers of a gifted power. He had heard it said that Mongán was not the son of the king, but the child of Manannán himself. He had heard it said that Mongán came and went from the Islands of Promise at will, sharing the skill of his sea-father’s knowledge. Some whispered that he could change his shape, becoming as insubstantial as the sea-foam. All said he was, even at his young age, a poet of great wisdom.

The brother – the most insignificant of the community, the least noticed, most infrequently missed – had moved closer to the two figures who stood so close in conversation. He had strained his ears to hear what words he could. Colmcille’s words were easy to understand. He was asking the stranger where he had come from. The reply made no sense. It must be that he had misheard.

“I have come,” the youth had answered, “from unknown lands and from known lands. I am here to ask you whether it is in this spot that knowledge and un-knowledge have died, have been born, and have been buried.”

The holy man was about to speak again. The young monk had hoped for help in understanding. “I have a question for you,” he had heard Colmcille address the youth again. ‘What is the history of this lough?” A simple question; although not one he could have answered, thought the young brother.

The young stranger was looking up, staring towards the water as if he were seeing into the past. “That I know well. It was yellow, it was flowery, it was green, it was hilly, it was full of drink, it was rich in silver, it was full of chariots. That was when I was a deer, when I was a salmon, and when I was a seal of great strength, when I was a roving wolf.” The young monk had tried to make sense of what he was hearing. Was this a calling up of the ‘Land Under Wave’? Were they all shape-shifters there?

The stranger had turned. The young monk had to creep closer before he could make out more of the words. The stranger, Mongán, (if it were he), was still speaking. “…sails, a yellow sail, it carried a green sail, it drowned a red sail under judgements of blood… Though I am not wholly of mortal parentage, do I not yet live in the mortal world?”

The two men turned away, walking into tree-shadow. The young brother could hear nothing more, and had returned to his day’s tasks. Even his psalter and the learning of the Latin could not be more bewildering than what he had just heard.

And now it was the dawn of another day. The stranger and the holy man were still deep in quiet conversation. They sat together on a rocky outcrop, their backs turned to the community. The fresh morning sun flashed one sudden gold spear, piercing the low cloud. The young monk briefly shaded his dazzled eyes. And when he looked up, the holy man sat alone. The stranger was gone.

The youngest – the most insignificant – of brothers did not hesitate. He ran like a child and sat quickly at the feet of Colmcille. “Father, who was that you were speaking to and what was he saying?”

“Nothing really,” replied Colmcille, carefully avoiding the young brother’s first question. He stood up yawning, stretching his arms. “I am not sure that I really understood a word he said.”

“But there must be a story to tell. You talked to him for long enough.”

“His story is not one for the world we are now making.” The saint began to walk back towards his waiting monks. The young brother followed him just catching the words that Colmcille added, almost under his breath. “Not for a while, at least.”

1 thought on “Colmcille and the Youth at Carn Eolairg”