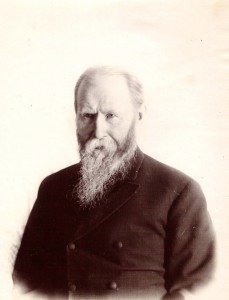

In our update on Ethliu, Mythical Women revisited: Series 5.3, we discussed the story of the birth of Lugh. The only available version of this story, Balor on Tory Island is to be found in “Hero Tales of Ireland” a book of orally narrated stories collected by folklorist and ethnologist Jeremiah Curtin and published in 1894. Jeremiah Curtin was born in 1835 in Detroit, Michigan, to Irish parents. His childhood was spent on a farm in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He later studied law, Slavic languages, and folklore in his time at Milwaukee University and at Harvard. He developed a lifelong interest in folklore and ethnology, publishing collections of aboriginal American stories, customs and folk practice of Siberia as well as his Irish story collections. An alternative strand of his work was tranlation. He was responsible for translating the literary works of the Nobel prize-winning Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz. Curtin was certainly something of a polyglot, speaking, perhaps, seventy languages, including Irish. However, Seán Ó Suilleabháin, in his introduction to Tales of the Fairies and of the Ghost World, collected from oral tradition in southwest Munster [1895] comments that he required “the aid of interpreters, as he never acquired a complete mastery of the various Irish dialects.”

Curtin travelled to Ireland in 1871, 1872, 1887, 1891, and 1892-93. He collected folklore, largely, from the West of Ireland, particularly, south-west Munster. He also visited the Aran Islands. In “Jeremiah Curtin: Cross-cultural, Collaborative Textual Production of Irish and Native American Mythologies’ – College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences,” Dr John Eastlake poses the question of how Curtin’s work compares with early Irish folklore publications, such as those by Thomas Crofton Croker, Patrick Kennedy, and Lady Wilde? He quotes Douglas Hyde’s comment on Curtin’s first Irish collection. Curtin has “’collected some twenty tales, which are told very well, and with much less cooking and flavouring than his predecessors employed.” In our explorations of Curtin’s Irish re-tellings, undertaken in support of Series 5.3, Ethliu revisited, we would agree. The stories do read well, although we find ourselves verbally editing out the unnecessary ‘Erin’. The stories, as he gives them, retain the patterns of their verbal origin and he has chosen not to sprinkle them with misleading Anglicised spellings of ‘ local dialect’ words, as can be found in other folklore collections from the period. Indeed, in a time when certain English scholars were describing even the great Irish saga texts as ‘low’ and as ‘having no literary value whatsoever’ the American, Curtin’s attitude and approach is refreshing. Curtin, in his exploration of mythology, sought for a a unified theory. He argued for a “common origin for human consciousness accessible, through the applied and ‘scientific study of mythology”. To achieve this, Jeremiah Curtin did set about collecting stories from a variety of cultures, especially Native American creation mythologies. By adding the Irish stories to this broader canvas he was able to step back and to recognise the deep and ancient roots that were still discernible in contemporary oral folk tales. This he demonstrated in his introduction to Hero Tales of Ireland (1894). Curtin says

“Of the pre-Christian beliefs of the Kelts not much is known, yet and with certainty. What we may say, at present, is this, that they form a very interesting variant on that aforementioned Ecumenical religion, held, in early ages, by all men. The peculiarities and value of the variant will be shown when the tales and literary monuments of the race are brought fully into evidence.”

Curtin was a man of his time. However his structuralist, comparative approach to his material was quite ‘modern for the time of publication. Indeed, he showed a sympathy for the Irish stories, even showing awareness of their importance in the landscape,i.e. their inherent ‘Dindshenchas’ nature. In the introduction to Myths and Folklore of Ireland [1890] (rep. edn. 1968): he adds,

“A mythology, in its time of greatest vigor, puts its imprint on the whole region to which it belongs; the hills, rivers, mountains, plains, villages, trees, rocks, sprAmazonings, and plants are all made sacred.’”

Over a century later, his folklore collections are more than curiosities. They are valuable recordings of oral re-tellings that might have otherwise been lost to us today. We have chosen two of Curtin’s retellings to explore further in two recorded conversations following on from our update podcast episode, Ethliu revisited. The first is called Elin Gow, the Swordsmith and the Cow, the Glas Gainach. The story contains many elements found in The Birth of Lugh from Balor on Tory Island, although the child, Lugh is replaced by Cormac and we find out how the smith (here called Elin Gow, rather than Goibniu) ,gets the cow in the first place. This story can be found in Myths and Folklore of Ireland . which is available to download or to read online. The second story is from Irish Folk Tales and is titled, The King of Erin and the Queen of the Moving Wheel. This intriguing, if somewhat convoluted story also enriches our understanding of the figure of Ethliu. Even more interesting is the Queen of the Moving wheel and her relationship with her son, whom she names and trains in a manner even more marked than the character of Arianrhod,in the Welsh story of the birth and childhood of Lleu. (The fourth branch of the Mabinogion). The story we have used in our second recorded conversation The King of Erin and the Queen of the Moving Wheel ,is not available online. We have been working directly from Isolde’s copy of the book. A few second hand copies are available through Amazon,

“I don’t know whether to blame the author or myself, but I find my appetite whetted but ultimately not fully satiated when I read this generous collection of entertaining–if common as dirt–Irish folktales. When one owns as many mythology, anthropology, and folklore books as I do–and is cursed with an eidetic memory–stuff congeals until one is about to cry. I read a Curtin story, putatively fresh, and find myself recognizing an episode from a French tale, a motif from a Russian tale, a character type from a Swedish tale. I know, I know, the Indo-European motifs are largely parroted over and over, albeit in sheep’s clothing, in various milieux. But Curtin could have done a better job of protecting me from this heavy dose of sameness by trying a bit harder to cull some, perhaps, less typical tales. I know they’re out there: the author must resist the temptation to deliver tales that, while artistically quaint or rich in some wise, are entirely repetitive of motifs that the well-read folklore enthusiast is more than apt to have digested over and over in multiple, vaguely differentiated forms. So, all in all, it’s good stuff, but I can’t say it’s terribly original.”