I have always liked round houses.

Since, as a child, I first discovered that there were mysterious wicker chests of red-gold gem stories tucked away, unregarded, behind the marbled classical tales of fabled Greek heroes, I wanted to know more.

But the stories from Wales and, above all, Ireland were hard to find, and even harder to read. In my “home counties” English childhood, names such as Conchobar, Manannán and Loegaire, seemed impossible to pronounce, and their context even more difficult to imagine than the far more ancient world of Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

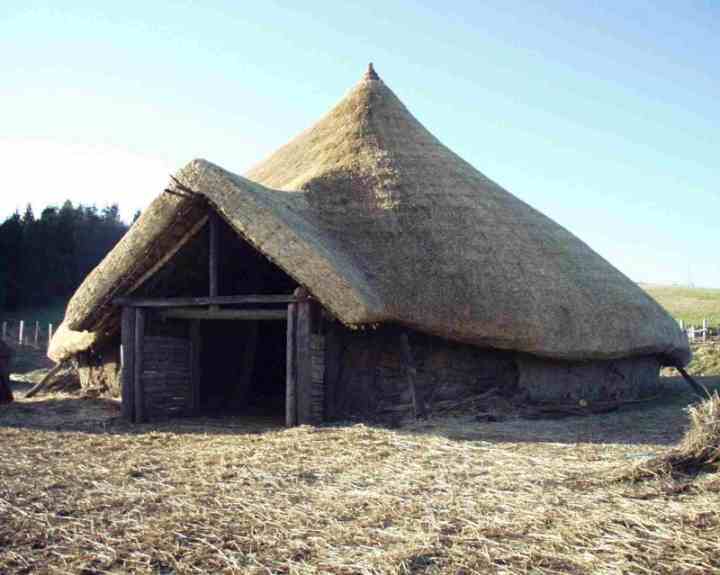

In the 1970’s I was inspired by the work of archaeologist, Peter Reynolds, at Butser ancient farm.

Here, at last, was a context for these rich and complex stories. I even seriously considered applying for a place on the BBC’s 1977 “Living in the Past” project, in which a group of families lived in an Iron-Age-style community for over a year. Peter Reynolds, himself, helped to train the participents in the many new skills they would need during their thirteen-month adventure.

It was a fascinating project, but perhaps, in hindsight, the family illness that prevented my application was for the best. However, I often took classes of primary-age children to Butser. Sitting in a Roundhouse, in costume, telling episodes from the old tales, was an inspiring experience, for me at least. I left my post in England in 1989 to move to Ireland. At the time, my intention was to build my own roundhouse and to initiate what we advertised at the time as “The Celtic Living Project”. The project developed a life of its own and grew in some exciting and unexpected ways, including a wide variety of workshops and theatre-based projects, including our “theatre in the street” version of part of “the Book of Invasions”. I sometimes think we were too busy to complete the building of the roundhouse.

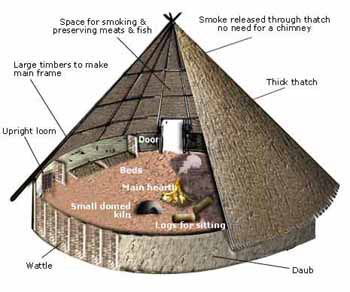

I was also privileged to spend occasional weekends in the roundhouses at Craggaunowen, “The Living Past”, archaeological open-air museum  in County Clare, founded by John Hunt. It was a great experience but sleeping in the structures led me to a realisation of just how smoky they could be. Sore eyes would have been common if the reconstructions are authentic. It was Peter Reynolds who established the danger of smoke-holes in roundhouse roofs. Smoke-holes, he found, have the tendency to transform them into blast furnaces so I guess sore eyes was just something to get used to.

in County Clare, founded by John Hunt. It was a great experience but sleeping in the structures led me to a realisation of just how smoky they could be. Sore eyes would have been common if the reconstructions are authentic. It was Peter Reynolds who established the danger of smoke-holes in roundhouse roofs. Smoke-holes, he found, have the tendency to transform them into blast furnaces so I guess sore eyes was just something to get used to.

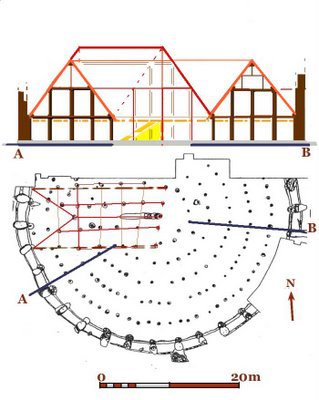

I like roundhouses, as I said, but there is a problem. The ability to visualise a variety of possible interpretations of a site must be a core skill for the archaeologist. Without the ability to mentally rebuild structures from post-holes, soil discolouration, or at best a few scattered potshards, Iron Age archaeology might become a muddy and tedious slog. Fortunately, archaeologists are generally enthusiastic, imaginative and optimistic types. Would they put up with the mud if they weren’t? However, archaeologists can only speculate so far. Reconstruction must be based on good evidenc,e and information is sketchy for this period. It is still a mysterious and misty time, particularly here in Ireland, where there are relatively few Iron Age sites, and even these have some very unexpected features.

I suppose that explains why reconstructed roundhouses often feel as though they are trying to look two thousand years old; dusty and monochrome. And yet, the texts clearly describe magnificent buildings, richly decorated, glittering in gold and bright bronze. There are references in Bricriu’s Feast to sumptuous fabrics, carved wood and fine finishes. There is nothing dusty and dull in this hall, or any of the other feasting halls described in the text.

These texts were first written down around the 9th century, but the stories they contained told of an ancient epic age of heroes; the “long-ago” time of Conchobar and Cú Chulainn. The process of romanticisation could be compared to the revival of the tales of King Arthur by Edward III. To this day, Arthur is generally portrayed in high medieval style rather than in Romano’-British garb, and we can thank Edward (and Mallory) for that.

Another analogy would be Homer’s tales of ancient Troy. It was long wondered if the orally recounted tales had held any memory, however distant, of epic and heroic events. Heinrich Schliemann certainly believed so, and went searching for the site of Troy. The story of his excavation is well known. He left the site in a bit of a mess, perhaps, and missed (or partly destroyed) the most likely stratum of Homeric Troy, but he was a visionary man of his time. The main point is that the old tales had retained elements of historical interest.

Doubtless, there is plenty of evidence of later building styles in the Irish texts. There is the reference to the magnificent glass windows of the hall. There are twelve such windows in the description of Crúachán. Bricriu’s hall also has a ‘high” room, translated as a “solar”, a grianán, in the text. Is this the medieval solar, the room that lead to the development of the main living rooms of the house, whereas the great hall shrunk down to a mere entrance vestibule? Probably it is, although archaeologists now think that Iron Age roundhouses may well have had upper platforms in their roofs.

So do the texts just describe a literary and fanciful imagination of a glorious heroic past, or can they tell us anything of an earlier time? Can we find anything that will help us to more clearly visualise the context of the Iron Age roundhouse and its interior living space?

Perhaps they can. The stories, although now in a literary form, show strong indications of a long oral tradition in terms of their structure, content and just their sheer “tellability”. Oral stories have been shown to pass on surprising amounts in terms of theme and detail over many generations, as we have discussed in previous podcast episodes. (See, for example, “Corpse Carrying for Beginners“.)

I also take heart from the quality of Iron Age artistic technology. The superb metal work, especially ornate horse-harness and other fine fittings that have been found, along with personal jewellery and household objects, indicate a culture of richness, even opulence, at least among the wealthier classes. It is hard to imagine these gorgeously-apparelled people sitting around a murky fire on a dusty floor.

There are texts available that provide descriptions of houses from the early Christian period. Fergus Kelly, in Early Irish Farming, quotes from the Críth Gablach, a law text dating from the 7th century, not so distant from the date of Fled Bricrenn. The text gives the appropriate dimensions for a house and contents according to the status of the owner, For example, the mruigfer, the most prosperous grade of farmer, should have a house of 27 feet in diameter, whereas a king’s status would demand a house with a diameter of 37 feet and having twelve bed cubicles. This matches the description of Bricriu’s hall. This hall is therefore clearly intended for a king, as a noble would only be expected to have eight bed cubicles.

So circular houses were still the norm in the 7th century, and from their descriptions here and archaeological excavations, not too different from Iron Age dwellings from around five hundred years earlier. To be fair, in his notes, (Early Irish Farming, p.361, note 9) Kelly points out that there is evidence of rectangular dwelling houses from about 800 CE.

Early Irish Farming has more to say concerning houses of the period. The whole book makes extremely interesting reading.

Other relevant evidence comes from the 2012 dig at Dundrum Castle, County Down. This was a joint excavation between archaeologists from Queens University Belfast and Channel 4’s Time Team. To quote Francis Pryor from Time Team;

Personally I was interested to see whether the Norman builders had erected their circular keep on a virgin hilltop or somewhere that was already important to Irish communities in the area. And my suspicions were confirmed. Although I say so myself, it’s a splendid film with some really significant academic discoveries. We always knew Dundrum was important, but after our three-day stay there, we now know that for certain.

What the team found was the stone foundation for a good sized circular structure of the 8th or 9th century feasting hall. Animal bone debris suggested evidence of meat consumption . It is not hard to imagine the tale of Bricriu’s feast recounted at feasts in this hall; a local tale of heroes, and one to keep a replete audience entertained. The archaeological notes for this dig are not yet available but you can still watch the episode on 4OD.

While the texts are, in no way, archaeological handbooks, they allow us as Story Archaeologists to explore the stratified levels of the stories, both oral and literary, and to enrich and deepen our understanding of these wonderful tales from our 21st century standpoint.

A Feast of Mead-circling halls

Several feasting halls are mentioned in the Fled Bricrenn text. There is a full list of links at the end of the article for further reading.

Dundrum Castle, Co. Down

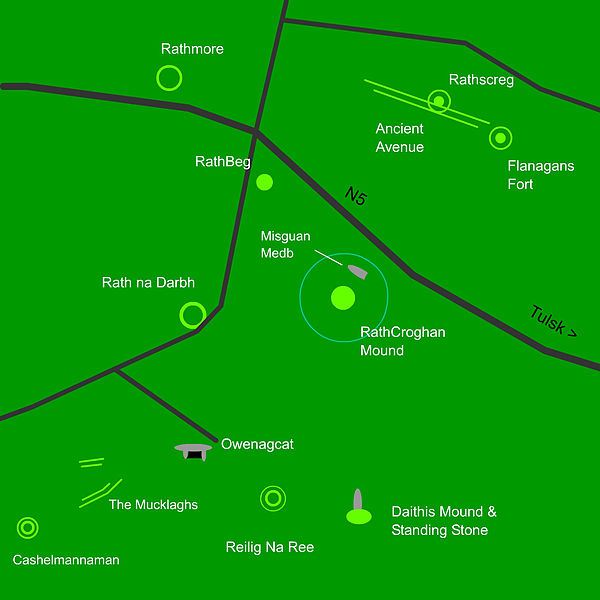

Crúachán, Co. Roscommon

John Waddell, Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at NUI Galway, is closely associated with the Crúachán complex. We have uploaded a PDF document in which he describes the features of the area.

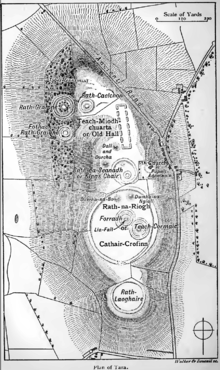

Tara, Co. Meath

The Megalithic Ireland website gives a good description of the complex. You will need to navigate to the “Meath” link in the sidebar, then the “Hill of Tara” link.

Emain Macha, Co. Armagh

This spectacular site, archaeologically speaking was discussed in Series 1, Episode 2, “The Story of Macha“. There is also a related article about the site itself.

The Iron Age Roundhouse

The Ancient Technology Centre‘s site has a good page to explain current thinking on roundhouse construction.

I also like this animation of an Iron Age Roundhouse’s construction on the BBC’s history page.

And because every archaeologist and Story Archaeologist should keep an open mind, and be prepared to examine all options, I offer a completely contrary view of early buildings from structural archaeologist, Geoff Carter. He has some startling opinions, and I feel that there is plenty of reliable evidence to support the more conventional view, but I enjoyed the site.

After all, back in the 70’s and 80’s, when encouraging young children to think critically, I used to tell them “Who knows for certain? Although it may be extremely improbable, perhaps some dinosaurs even had brightly-coloured feathers”. That turned out to be most unexpectedly true!

It is always worth thinking outside the box, if only to see what is lurking there.

Enjoy!

July ’13

Links:

Butser Ancient Farm: http://www.butser.org.uk/

Craggaunowen, “The Living Past”: http://www.heritageisland.com/attractions/craggaunowen-the-living-past/

Time Team’s dig at Dundrum Castle, Co. Down: http://www.channel4.com/programmes/time-team/4od#3513438

Visitor information on Dundrum Castle, Co. Down: http://www.virtualvisittours.com/dundrum-castle/

John Waddell, NUI Galway, archaeological description of the site of Crúachán, Co. Roscommon:

https://storyarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/waddell_2009_rathcroghan.pdf

Description of site of Tara, Co. Meath, on Megalithic Ireland. (Go to “Meath” link in the sidebar, then the “Hill of Tara” link):

http://www.megalithicireland.com/

Series 1, “Mythical Women”: Episode 2, “The Story of Macha”:

https://storyarchaeology.com/2012/07/05/acallam-na-neces-episode-2/

Article on Emain Macha / Navan Fort related to above episode:

https://storyarchaeology.com/2012/07/05/navan-fort-emain-macha/

The Ancient Technology Centre’s page on Iron Age Roundhouses:

http://www.ancienttechnologycentre.co.uk/ironageroundhouse.html

Animated construction of an Iron Age Roundhouse:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/interactive/animations/ironage_roundhouse/index_embed.shtml

Geoff Carter, structural archaeologist, explains his theories on Iron Age architecture:

http://structuralarchaeology.blogspot.ie/2009/06/30-not-going-with-flow.html