Have you ever heard of a Sheela na Gig?

Irish composer and Professor in Music at Middlesex University, Benjamin Dwyer gives us more details of the phenomenon. IRELAND has more Sheela-ha-gigs, audaciously dfiant female stone carvings than anywhere else in Europe. Hidden away for centuries they are now resurging with ÉIRÍ – the arts competition and research project that anyone can get involved in with 10,000 up for grabs.

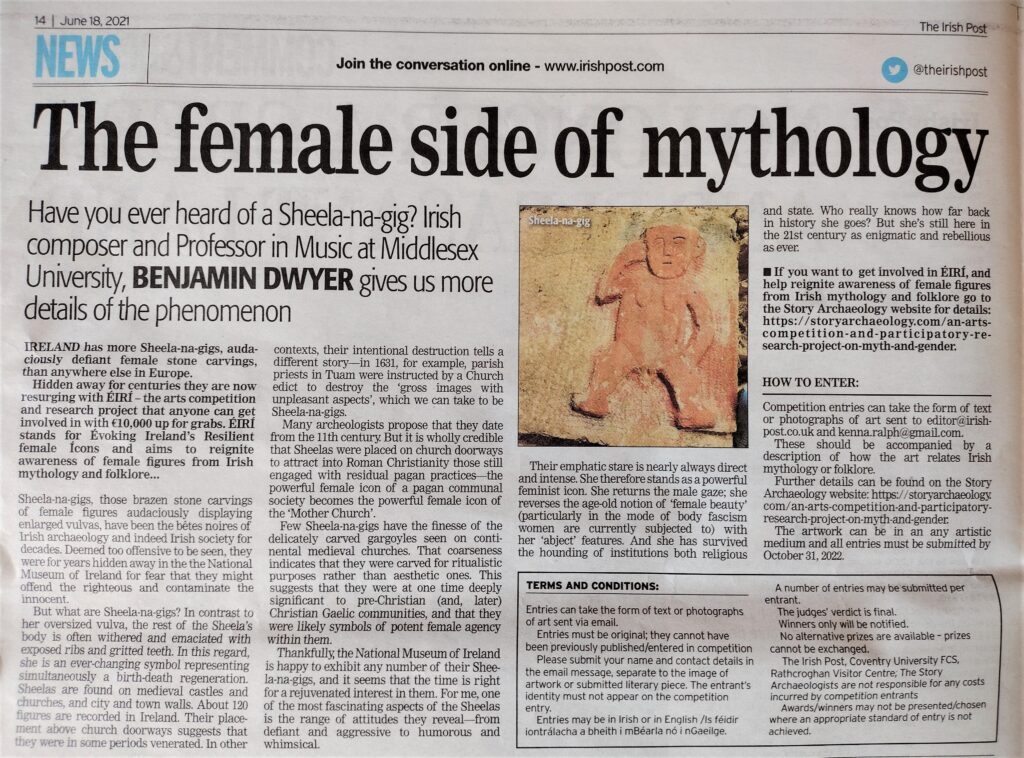

ÉIRÍ stands for Evoking Ireland’s Resiliant female Icons and aims to reignite awareness of female figures from Irish mythology and folklore. Sheela-na-gigs are brazen stone carvings of female figures audaciously displaying enlarged vulvas. They have been the bêtes noires of Irish archaeology and indeed Irish society for decades. Deemed too offensive to be seen, they were for years hidden away in the bowels of the National Museum of Ireland for fear that they might offend the righteous and contaminate the innocent.

But what are Sheela-na-gigs? In contrast to her oversized vulva, the rest of the Sheela’s body is often withered and emaciated with exposed ribs and gritted teeth. In this regard, she is an ever-changing symbol representing simultaneously a birth-death regeneration. Sheelas are found on medieval castles and churches, and city and town walls. About 120 figures are recorded in Ireland. Their placement above church doorways suggests that they were in some periods venerated. In other contexts, their intentional destruction tells a different story—in 1631, for example, parish priests in Tuam were instructed by a Church edict to destroy the ‘gross images with unpleasant aspects’, which we can take to be Sheela-na-gigs.

Many archeologists propose that they date from the 11th century. But it is wholly credible that Sheelas were placed on church doorways to attract into Roman Christianity those still engaged with residual pagan practices—the powerful female icon of a pagan communal society becomes the powerful female icon of the ‘Mother Church’. Few Sheela-na-gigs have the finesse of the delicately carved gargoyles seen on continental medieval churches. That coarseness indicates that they were carved for ritualistic purposes rather than aesthetic ones. This suggests that they were at one time deeply significant to pre[1]Christian (and, later) Christian Gaelic communities, and that they were likely symbols of potent female agency within them. Thankfully, the National Museum of Ireland is happy to exhibit any number of their Sheela-na[1]gigs, and it seems that the time is right for a rejuvenated interest in them.

For me, one of the most fascinating aspects of the Sheelas is the range of attitudes they reveal—from defiant and aggressive to humorous and whimsical. Their emphatic stare is nearly always direct and intense. She therefore stands as a powerful feminist icon. She returns the male gaze; she reverses the age-old notion of ‘female beauty’ (particularly in the mode of body fascism women are currently subjected to) with her ‘abject’ features. And she has survived the hounding of institutions both religious and state. Who really knows how far back in history she goes? But she’s still here in the 21st century as enigmatic and rebellious as ever.

If you want to get involved in ÉIRÍ, and help reignite awareness of female figures from Irish mythology and folklore go to the Story Archaeology ÉIRÍ, competition page for details.

Competition entries can take the form of text or photographs of art sent to editor@irishpost.co.uk and kenna.ralph@gmail.com. These should be accompanied by a description of how the art relates Irish mythology or folklore.

View all of the ÉIRÍ Competition articles from the Irish Post